A Conversation With ... Phil Nimmons

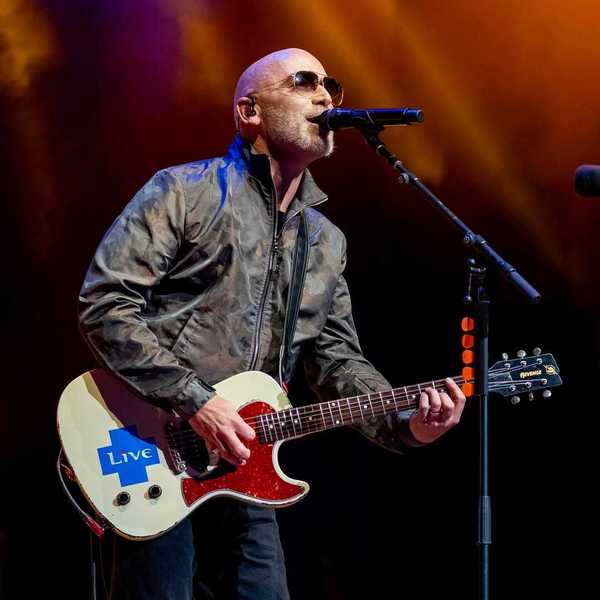

Just out is an album paying tribute to a Canadian gem and living jazz icon, Phil Nimmons, entitled To The Nth, the brainchild of grandso

By Bill King

Just out is an album paying tribute to a Canadian gem and living jazz icon, Phil Nimmons, entitled To The Nth, the brainchild of grandson pianist/arranger Sean Nimmons-Paterson. The eight selections draw from a wealth of compositions that reflect the personal relationships Nimmons had with his beloved Canada and family.

Younger Nimmons assembled a stellar cast – Kevin Turcotte, trumpet, flugelhorn, Tara Davidson, alto and soprano saxophones, clarinet, Mike Murley, tenor saxophone, William Carn, trombone, Perry White, baritone sax and bass clarinet, Sean Nimmons, piano, Fender Rhodes, Jon Maharaj, bass, and Ethan Ardelli, drums. The sound is authentic Nimmons ‘N’ Nine.

Nimmons just retired from teaching at 96 years of age and still engaged in the art that gave us so much and him so much joy. We spoke in 2005 and his words ring true today.

Clarinetist, composer, conductor and educator Phil Nimmons was born in Kamloops, British Columbia, on June 3, 1923. He later graduated from the University of British Columbia and went on to study at the Julliard School of Music in New York City and at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto. Nimmons is a founding member of the Canadian League of Composers, established in 1950, and was a co-founder with Oscar Peterson and Ray Brown of the Advanced School of Contemporary Music in Toronto from 1960 -1966. Along with leading and composing for his various bands, he is currently Director Emeritus of Jazz Studies at the Faculty of Music at the University of Toronto. His compositional work includes contemporary classical works and over 400 original jazz compositions.

Bill King: Reading through your discography with titles like Atlantic Suite, Harbours, Islands, Tides and Horizons, PEI, Jasper and Caribou County Tone Poem, one can’t help recognizing you have a great love for this country. Does the remarkable landscape influence your composing?

Phil Nimmons: In the beginning, as far as writing is concerned, I don’t feel that’s necessarily so. I think the creative process is in all of us in some shape or form. In my case, I think there was this drive to be creative right from my teens.

I think the landscaping tendencies started when I began writing dramatic music for the CBC in Vancouver in the late ‘40s. I wrote some things at the time for Dick Diespecker who was a war correspondent and had written a program called Anthology. I wrote dramatic music for that before I went to New York and studied. That would have been around 1944 or ‘45.

Leaping beyond that, I eventually came to Toronto to study at the Conservatory and ended up writing for J. Frank Willis, who was a producer of dramatic shows on the CBC who came from Halifax. At First, we did nothing but sea stories.

Even before I got to the east coast, I felt I had been transplanted from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic. We did a program called the Days of Sail, which was all about the sailboats and slave trade. So I wrote about Peggy’s Cove, Lunenburg and Sable Island before I got there.

Eventually, my sister and her husband became residents at the University of New Brunswick. I would say, not overtly, but by osmosis. I’m developing a relationship with the geography of the country. People still ask when I am going to do something about the Pacific Ocean, which I guess is in the back of my mind.

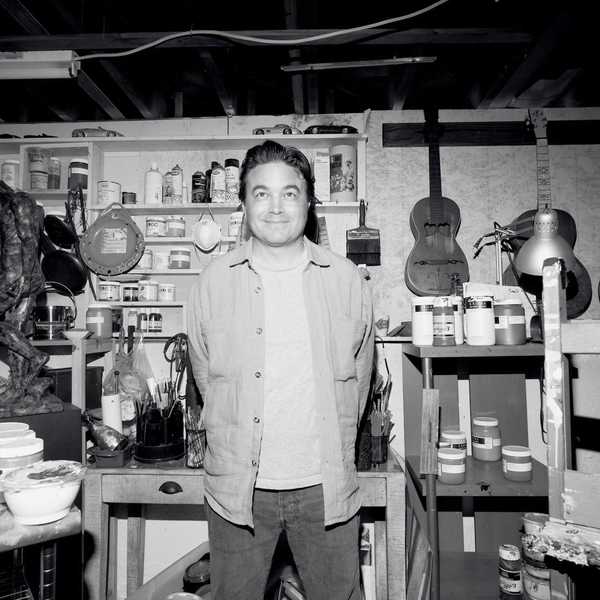

B.K.: Do you have a favourite workplace that inspires you - a room or locale?

P.N.: No, not necessarily. When you ask that question, I wonder how the heck I created some of those lovely things when they came from my debris-filled studio in the basement. It was a mess of papers, pens and ink with cigarette burns on the ivory keys of my piano and glass stains from drinks.

I do like having a piano handy when I get an idea. I really work it to death, trying to see how many mutations I can get into it. Eventually, I often end up doing the original idea.

I used to work at it hard and shout up to my wife, Noreen. ‘Listen to this.’ Then I’d say, ’Listen to this other one.’ Do you hear it? It would be only a difference of a 16th note or something. Noreen would reply, ‘Just write it.’

I know when I teach, I tell my students to be quite curious about the potential for variations. But I can do that in my head, it doesn’t matter where I am.

B.K.: How does the writing process begin, with a motif, an unusual harmonic sequence?

P.N.: All of those things could be sources, but ideally it is to find some kind of motif that is the seed so full of potential that once you start to work with it, it almost writes itself. I’ve had a couple of occasions where that happens. The musical seed will be strictly musical. In addition to that, I look for all kinds of ways of developing ideas, like maybe taking my birth date and make a tone row out of it. You mentioned Caribou Tone Poem, well, that’s based on my birth date and mixed with thoughts.

Being born in Kamloops, I have really vivid memories. We left there when I was seven in 1930, but my grandparents remained. We used to go back and forth all of the time. I remember Kamloops being so hot you could almost fry an egg on the sidewalk. It’s located on that plateau between the coastal range and the Rockies where all of those cities like Kelowna and Vernon are. I also remember two mountains, Peter and Paul, which were north of where we lived. There used to be great electrical storms with the lighting bouncing from one peak to the next.

I use my birthday as a tone row and make certain changes to it, I might come up with something that’s not precisely based on my birthday, but becomes the initial motivator to do something different. Eventually, you’ll come up with something that has potential for development whether melodically, harmonically or rhythmically. I’m a great believer in form. It’s probably the most important thing everywhere - even our lives have to have some kind of form to communicate effectively.

B.K: If you were to sit down at this moment and begin a long-form piece, what do you think the mood and tone of the exercise would be?

P.H.: Thankfulness. I’m in that particular mood at this particular time.

B.K.: What would be the instrumentation?

P.N.: Whatever the budget could afford. The experiences I had with the CBC, writing dramatic music without me knowing, was the greatest teacher I had because I heard everything I wrote at the time. Depending on the content of the show or the budget, the instrumentation I would write for could be anything from a trio to a symphony orchestra. One of the first things I did for J. Frank Willis was The Cricket on the Hearth the Charles Dickens thing. We used English horn, harp and violin or viola. I had never written for harp before, so I got out my Cecil Forsyth orchestration book.

Even when Nimmons ‘N’ Nine was formed, the plan was not necessarily to include 10 musicians. When it first came together, there were only nine people. Then, Eddie Karam comes to town from Ottawa. I can remember Jerry Toth coming to me saying, ‘We’ve got to get this guy in the band.’ Everyone was a studio musician and they were all such great musicians that could play anything I wrote.

Eric Traugott is just mind-boggling in this regard. I have not met another trumpet player who had as great a sound from G above the staff right down to a G below the staff that can be done within a bar. We never took the horns out of our mouths. Obviously, we were much younger then and played all the time.

B.K.: How much has your writing changed through the years and can you give an example?

P.N.: I don’t know if it’s changed so much. I still try to write melodically. I try to write interesting parts for every player right down to the fourth trumpet player.

B.K.: Was Robert Farnon around then?

P.N.: Yes, I knew Bob at the time. I had two dear friends in Vancouver while I was growing up as a teenager and working at the CBC. I worked with the Ray Norris Quintet when I first started and we had a comedian who played the piano while the late Barney Potts sang. We began lifting Nat Cole recordings.

I was also in Vancouver CBC Chamber Orchestra and two individuals, in particular, became great friends of mine – John Avison, who was the conductor and a great classical accompanist and Lawrence Wilson, who was a trumpet player who was in the mainstream back in the late ‘40’s who eventually became vice-president of the CBC. We would do shows and afterwards, go to their homes and listen to recordings from Palestrina to Schonberg. Here, I was 15 years old, hearing people talk about music all the time – I just soaked it up like a sponge.

B.K: What has been the most difficult assignment to conquer and why?

P.N.: There’s nothing specifically that comes to mind because I’ve done such a variety of things. I did a Commonwealth thing a way back that I had to research and come up with all the national anthems from all the Commonwealth countries, back when there were quite a few of them. It was a difficult assignment and I didn’t want to do but I did.

Fortunately, I learned awhile back I had to do things I may have not wanted to do to pay for the monkey on my back, which was jazz. I wrote some Gilbert and Sullivan things and rather enjoyed it even though it wasn’t stylistically something I really did relate to. The same can be said for opera. I have done overtures from operas and that’s been an education. I’ll tell you one thing I find difficult is when someone sends me a tape to lift that’s been generated electronically through a synthesizer. I have to keep listening to it over and over because I don’t have perfect pitch, but instead a very good ear, and that’s like torture.

I begin to wonder if every old guy generation to generation has gone through this. I try to cope with it. I ask myself, is the problem because I’ve grown up with acoustic sounds.

B.K.: I think you got caught in transition. Electronics erased the acoustic studio musician in the 1980s and ‘90s. Now, there’s a realization we can work with both. For jazz players, it’s back to acoustic.

P.N.: Fortunately, I may not be able to comment on the question truthfully because I’m 81. I’m just so thankful for the things that are happening.

B.K.: If you had a choice of musicians throughout history to assemble under one roof to play your music, who would be on the bandstand?

P.N.: That would take a lot of thought. At first, I think I would like to get people who relate to my philosophies, but then I realize it doesn’t matter. What matters is what happens on the bandstand. I’d like to thank Duke for setting the pattern. It didn’t matter when the band showed up as long as they got there. I was privy to a few events when we had the school with Oscar Peterson and Ray Brown. We’d go to Chicago for meetings and stay at the Palmer House. After they finished playing the London House, we’d go down to the south side of Chicago around one o’clock to hear Duke’s band play.

One night, we went down there and the only person to show up was Duke, so we went home. He was just so great as opposed to other leaders I know that just get some uptight. I imagine a third world war might have started on Tommy Dorsey or Benny Goodman’s bandstand.

In Nimmons ‘N’ Nine, I had all of those wonderful people starting with Roy Smith, Jerry Toth, Ed Karam, Jack McQuade, Murray and Teddy Roderman and Ross Cully. When the band changed, Rob McConnell was in the band along with Guido Basso, Freddie Stone, Herbie Spanier, Moe Koffman, and Eugene Amaro. All of those fellows brought something different to the band.

I was blessed to take something from all of these people. I try to keep an open mind, which sometimes makes things difficult. But if you do, the benefits are so great. I have lasting relationships with all of these people.

B.K.: You suffered a great loss with the recent passing of your longtime companion Noreen. Has teaching and performing helped ease the pain?

P.N.: Yes, but I’m still dealing with the process. I will cope, but I’m not quite prepared at all times. I’m very lucky to be busy which gets me out of the house and away from being by myself. At the same time, I do that because I can’t help but think this would not have been possible without her. I drank my butt off up until 1970. I did a very good job of being down in the basement writing. I’d come upstairs and Noreen would say to the kids. ‘That’s your dad, not the plumber.’ She had to put up with me and she did.

In retrospect, she looked after the kids. I came from the old school where the woman stayed home and raised the kids and the man worked. I even sold real estate for two or three years. That was not difficult to do because part of my philosophy was that when I got married, I made a contract with a young lady that we were going to do something together, and I would have to do whatever it took to fulfill. It’s very easy to say, but not as easy to do. You never know what will happen. She put up with so much, but I don’t think I’m unique in that respect.

B.K.: Loving relationships can be critical in freeing the soul to create and release that which is hidden below the surface. Was Noreen often the keeper of the key?

P.N.: No, I think we both were. I say that because I think that’s a deep desire as well as something I believe in. Nothing happens without two and a lot happens with three. Two people can start, but an odd number can put the vote up for grabs. It creates a lot more interest.

Being the fundamental part of the pyramid as the parents of this family or household, whichever way it goes, it really took the two of us. There has to be a lot of bending, giving and compromise because of what you want to achieve. I think she bent a little bit more than I did, but I was eight years older than she was. Maybe that gave me a certain sense of conviction.

Plus the fact, I say with great profundity, we’ll never be as brilliant as they are. The male is such a dolt by comparison and I really believe that. Some people ask the question: ‘Would you have done things differently knowing what you know today?’

Of course, you would, but that will never happen.