Blue Note Records: Beyond the Notes - Uncompromising Expression

A beautifully conceived new film by Swiss film-maker Sophie Huber documents the pioneering jazz label. Here Bill King resurrects an insightful chat with a Blue Note mainstay, Horace Silver.

By Bill King

Blue Note Records debuted in 1939, with a name derived from the “blue notes” that make up the sound of jazz and blues, and went on to become one of the most original, successful and creative showcases for jazz these past 80 years. Much of the contrastive photography and cover designs are published in an illustrated book by Richie Havers – Uncompromising Expression; published by Thames and Hudson. Now comes the doc (Blue Note Records: Beyond the Notes) – a beautifully conceived film by Swiss film-maker Sophie Huber.

The film is a film absent what would seem the impossible - historical footage. Instead, Beyond the Notes relies on the iconic in studio images of Francis Wolff to recount the many sessions and the musicians who inhabited this insular world of uncompromising discovery.

Telling the story are contemporary interviews with trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, producer, historian and owner of Francis Wolff photo collection, Michael Cuscuna, saxophonist Lou Donaldson, contemporary hip hop jazz keyboardist Robert Glasper, Herbie Hancock, bassist Derrick Hodge, Norah Jones, sound engineer Keith Hodge, guitarist Lionel Loueke, hip-hop producer Terrace Martin, A Tribe Called Quest, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, drummer Kendrick Scott, Wayne Shorter, saxophonist Marcus Strickland, sound engineer Rudy Van Gelder, and producer and current president of Blue Note Records, Don Was.

When record stores were sanctuaries of discovery and brief meditation - the first thing that caught the jazz-eye were the record bins were those Blue Note covers that screamed jazz - designed by artist Reid Miles, who once worked for Esquire magazine. It was the graphic sensibilities and photographic eye of label co-owner and professional photographer François Wolff that captured musicians in natural surroundings; the recording studio and Miles’ keen use of fonts and modern design layout. Wolff used a Rollie medium format camera, a one or two lights set-up or a handheld flash to dramatize the artist at work and served to paint jazz a mysterious world inhabited by mostly men engaged in cerebral thought – as if they were well-dressed mathematicians bent on deciphering a complicated formula. And jazz was complex and growing more so as each new face signed on bringing an original pattern to the mosaic quilt.

There was a Blue Note sound courtesy of engineer Rudy Van Gelder. The piano sounded isolated and rich-toned, much the same on successive recordings – drums – crisp and forceful and horns – the star of the show – up front and tightly mixed. Label kingpins Alfred Lion, Max Margulis, and Francis Wolff played by their own set of rules – paying musicians for rehearsals and reviewing the music until it was ready for the studio - then allowing the players the necessary hours to complete – even working around players' schedule to make each session a solitary commitment of focus, integrity and creativity.

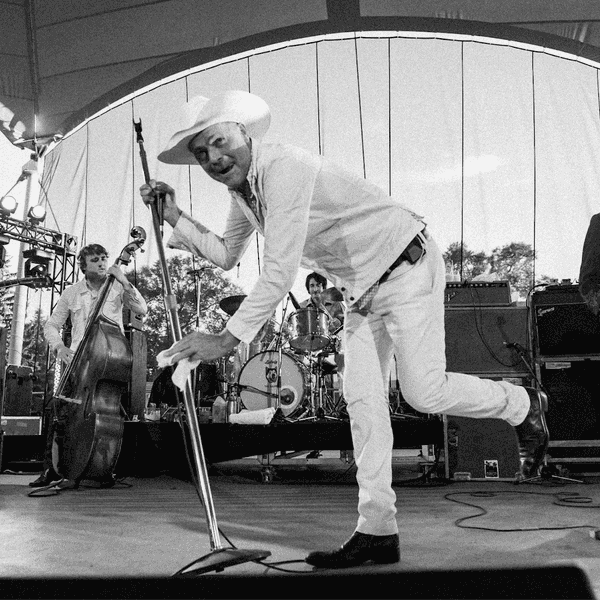

Blue Note was primarily a ‘hard bop’ label built around artists; Horace Silver, Jimmy Smith, Freddie Hubbard, Lee Morgan, Art Blakey, Grant Green, Hank Mobley, and others. It was also a launching pad for ‘new direction’ jazz composers Herbie Hancock, Andrew Hill and to the avant-garde stylings of Cecil Taylor, Sam Rivers, organist Larry Young, Eric Dolphy, and company.

Blue Note packaging, much like Impulse Records, which came bordered in large orange and black panels, Columbia’s contemporary art, either by the artist or borrowed, were 12 inches of intrigue. From the music deep in the grooves to the eye-catching sleeves and astute liner notes backside. They were high art listening panels.

For twenty plus years, Toronto DJ Curtis Bailey played a steady diet of Blue Note sides on his popular Saturday afternoon radio show, ‘All That Jazz,’ at CIUT FM 89.5. Bailey passed away in 2007 at the age of 64 and along with him went those crowded afternoon sessions of hard bop - those bending organ riffs and soul/jazz escapades of Jimmy Smith, Horace Silver, and Art Blakey. Bailey was a Blue Note man through and through!

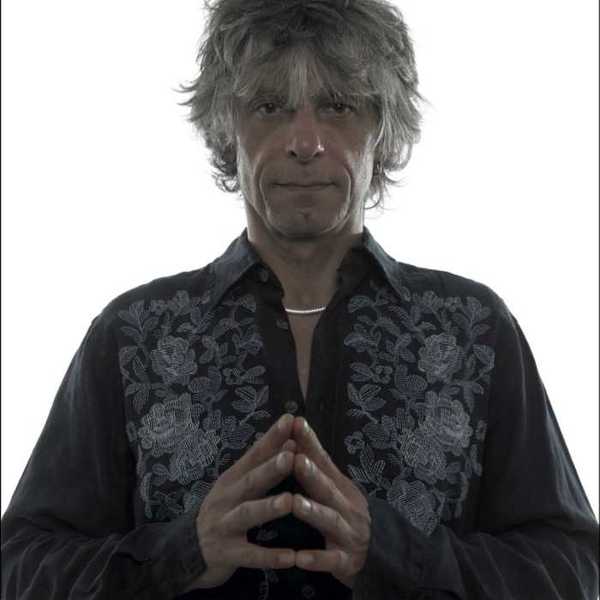

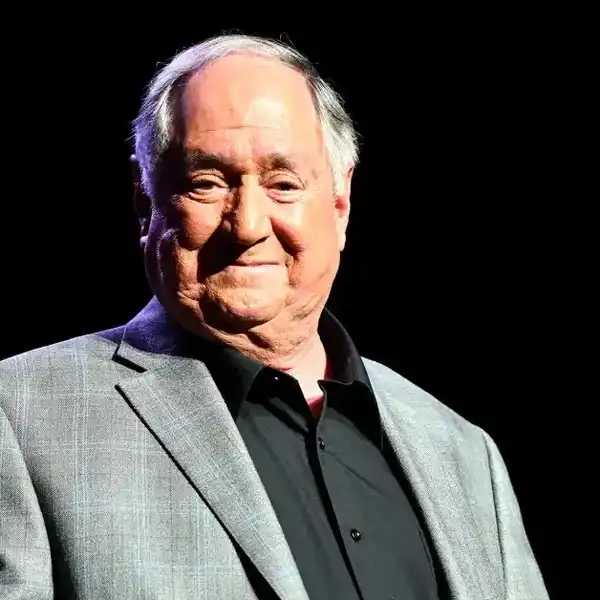

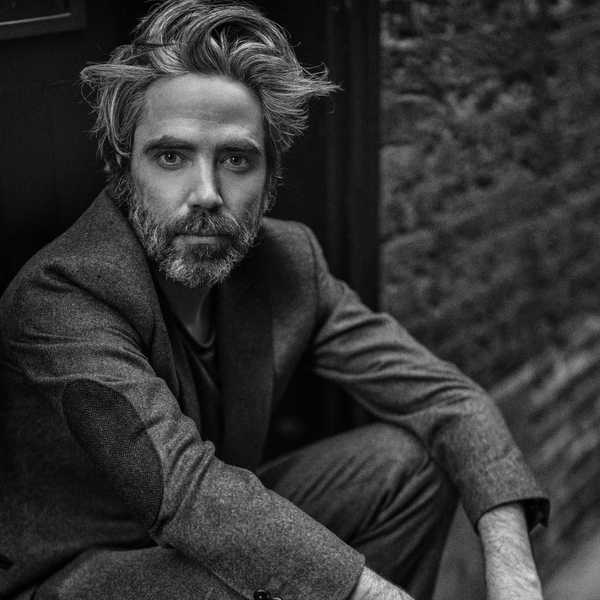

I spoke with one of Blue Note’s guiding lights, pianist/composer Horace Silver, in 1998 at a time when he was still fully engaged – composing and recording. Silver passed on this past June at the age of 85.

Silver was one of the leading advocates of the hard bop movement always exploring new territories with both his blue-toned compositions and arrangements. He was a long-time member of the Blue Note group spanning 40 sessions for the label as leader and sidemen over a 27 period until the label’s temporary shutdown in 1979. For more than four decades his quintets prominently featured trumpet and saxophone pairings. Silvers’ powerful percussive bass lines, forceful rhythms, punctuated piano accompaniment and lyrical melodic approach have produced numerous well-known jazz standards including; “The Preacher, Song For My Father, Senor Blues, Nica’s Dream and Sister Sadie.”

BK: There’s a spirit in your music which has continued throughout your career, what do you attribute this to?

Horace: It’s my love for the music. I love it with a passion. Whether I was famous or not, rich or poor, I’d always be playing this music. I got turned on when I was about 10 or 11 years old. My dad took me to an amusement park where I heard the Jimmy Lunceford Orchestra. That band sounded so great that day. They played beautifully with so much feeling and soul and precision; I said, “That’s what I want to be – a musician.” I committed that day and all through my teens it was music, music, music. It was all I wanted to do then, and it’s still all I want to do. I strive to write music that will stand the test of time.

BK: Your latest disc, Jazz Has A Sense of Humor, comes with lyrics but no vocalist. Were you anticipating people would sing along?

Horace: I intended to use some vocalists, but I couldn’t find anybody who particularly suited the music. It’s like casting for a movie. A director may try out one of the great actors like Marlon

Brando, but he may not suit that role, so he goes onto somebody else. All the singers I tried were excellent. I auditioned several, but none of them seemed to suit this material. They just didn’t grab me, so I did it without them, and put the lyrics in so people could sing along if they wanted to. If there is a recording artist out there that likes the tune, then the lyrics are there for them to record.

BK: Some excellent original pieces recall your great Blue Note sessions, particularly ‘Mama Suite’. The recording has caught on with the public and made it an international success. Are you surprised by the reception it is receiving?

Horace: Very happily so. Of course, you hope every album you do will be a success. This one has been on the Gavin chart at number one for seven weeks. I’m very proud and happy about that.

BK: What are the key ingredients in making the perfect Horace Silver composition?

Horace: You tell me that. I don’t know myself.

BK: Well, there’s a spark inside those tunes that get things happening.

Horace: It comes from all those great mentors who inspired me and continue to do so.

BK: There have been so many changes in jazz composition the past 50 years – swing, bebop, the modal thing, extended harmonics, free playing-yet you’ve stayed close to the blues and produced wonderfully eclectic songs that are a lot of fun to solo on. Why does the blues form hold so much appeal for you?

Horace: It’s a basic form and one that people can relate to, even non-jazz people. It’s my common denominator to reach the audience.

BK: “Ecaroh, Opus De Funk, Doodlin’, The Preacher, Home Cookin’, Cookin’ at The Continental, Sister Sadie, Psychedelic Sally, Nica’s Dream” and “Song for My Father” are just a few of your most memorable originals. Any particular favorites?

Horace: Not really. I look at my compositions as my children. I’m certain a person who has 16 kids loves every one of them equally. If I had 16 children, I’d love them and treat them equally. I’m grateful for those tunes which have become very popular, but there are others that aren’t as popular that I love just as much. They are fine compositions but have never caught on.

BK: How many cover versions are there of “Song for My Father?”

Horace: I couldn’t begin to estimate. I’m happy that there are so many, and people are still recording it. When I perform, I can’t get away without playing “Song for My Father.” If I don’t play it as a closing number, people go away very disappointed. And I hate to do that to them, so I always include it in my program. Songs like, “The Preacher,” were fairly well accepted when they came out, but it’s taken years for them to reach the stature they have now. They’ve become jazz standards.

“Nica’s Dream," "Strollin’” and “Peace” were all nice when they came out, but it took them a few years to do their thing and be recorded by other musicians.

BK: Two horns, trumpet, and tenor seem to be all you need up front to interpret the melody. Why does this combination hold such great appeal?

Horace: It’s the combination that I started out with, and it’s financially feasible. Let’s face it, in the jazz world, it’s not easy booking a big band. The hotel bills and flight expenses make it near impossible. I decided early in my career to work with a small combo because it was the best combination for my concept.

I also believe people expect to see me in that setting, although I have varied it over the years with the Blue Note albums like Silver and Brass, Silver and Wood, Silver and Strings, Silver and Percussion, and Silver and Voices. As well, the Hardbop Grandpop on Impulse featured a great seven-piece band that was again something a little different for the people who enjoy my music.

BK: It seems Cannonball Adderley and you explored similar territory, memorable tunes and soulful front men. Did you ever work together?

Horace: Very briefly. I made a record with Cannonball, his brother Nat and Oscar Pettiford. I think it was Cannonball’s session, but it was so long ago, I’m not sure. I was working at the Café Bohemia with Oscar and his band, and Cannonball and his brother came in one night. We’d heard about them, so Oscar asked them to sit in, and they broke the house up. As a result, Cannonball got a record session. Kenny Clarke was on drums, Oscar on bass, me on piano and Cannonball and Nat.

BK: During all the years of touring, which other jazz groups excited you?

Horace: Well, there was Cannonball’s group and Miles Davis’ band was really fine. So was Dizzy Gillespie’s. But in those days Miles was the forerunner of everything.

BK: You spent 1953 to 1979 with one record label, a rarity for any artist. Blue Note has just released The Horace Silver Retrospective. Did you have any input in the project?

Horace: Some. They called and said they were going to do it. Michael Cuscuna was in charge of it. He compiled the tunes and sent me a list to look at and said if there’s something that doesn’t meet your approval, we’ll change it. I went over the list and by and large he picked most of the tunes I would have chosen anyway. He picked the hit tunes. I think I made about three or four changes, but the continuity was well done.

BK: Any thoughts on Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff?

Horace: They were my good buddies. They were not only my employees but my friends. We used to go out and eat a lot. We loved good food. Alfred knew all the great restaurants around New York - he was a connoisseur. One night it would be Italian, the next Indian, German, Swedish smorgasbord, French. We’d usually rehearse the day before a session for timing, and afterward we’d always go to a fine restaurant to eat and discuss the session.

We’d talk about the different takes and the merits of say, take one, compared to take three, and make mental notes for the next day.

BK: What do you miss most about that era?

Horace: I didn’t realize it at the time, but just being alive in New York City when all those great musicians were there. There were such geniuses; Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, Art Tatum, Teddy Wilson, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, J.J. Johnson, Milt Jackson, Kenny Clarke, and Art Blakey. All those cats were in New York then. It was a great opportunity for a young man like me, in my early 20s, to be there, hobnob, and play with them. What a schooling that was.

BK: Are you excited about your relationship with Verve Records and does the state of the business differ from the old days?

Horace: It hasn’t changed much for me other than going from vinyl to CD. Ever since I started recording, I’ve been blessed in that I’ve been with companies that let me do my thing. I haven’t had anybody towering over me and telling me you should use so and so on trumpet. They don’t come to me and say, “Do this particular tune,” or we want you to record an album of Gershwin tunes. They respect my ability as a composer, as a leader, and as a player. They let me go on, do my thing, and tell my story.