ARETHA: Octaves Of Bittersweet Ecstasy

The following story, penned by Ritchie Yorke, first appeared in The Globe Magazine in 1969 and it perfectly captures the vibe of Aretha recoding in Miami's Criteria with Tom Dowd, Jerry Wexler, arranger Arif Mardin, her four-member vocal backing group the Sweethearts of Soul, and the Muscle Shoals rhythm section.

By Ritchie Yorke

The following feature is penned by the late Ritchie Yorke (see his particulars at the foot of this article), written in early November of 1969 and appearing that same year in the Nov. 15 edition of The Globe (and Mail) Magazine. In it, Yorke flies to Miami to capture the vibe in Criteria Studios where Aretha Franklin is recording her album, This Girl's In Love With You, aided by producers Tom Dowd, Jerry Wexler, arranger Arif Mardin and the Muscle Shoals rhythm section, augmented by Duane Allman on her riveting interpretation of The Band classic, "The Weight."

The feature also includes a Q&A with the Queen of Soul who died last month at age 76. In her responses, she proves to have been a big fan of many Canadian artists, including Oscar Peterson. The article is reprinted as it was originally published with permissions from both the Globe and Mail and the author's estate and in particular his widow, Minnie.

MIAMI. It is approaching 9 on Friday evening and North Miami is buzzing with black Cadillacs, overweight people and neon signs. Just off Dixie Highway and about half a mile from the ocean, five young musicians from Muscle Shoals, Alabama, are sitting around Criteria Studios, awaiting the arrival of Aretha Franklin— swigging Cokes and coffee.

At 9:15 the phone rings and Tom Dowd, one of Aretha's studio producers, snatches at it before the second ring. The musicians come to life. The call is from Jerry Wexler, the record producer who has made Aretha the biggest selling female vocalist in history. Wexler is in Aretha's suite at the Fontainebleau. He has bad news. Aretha isn’t feeling up to making the session. She is tired, and not in the right mood. It was the same last night.

By past standards, things are going well. Aretha has made it two nights out of four in her first studio session of any consequence in 1969. Two previous sessions— in January and April— have come to an unhappy end after a single day.

Dowd hangs up, scratches his grey beard and watches the musicians stream out the door, hands in pockets and eyes to the ground. They’ve been in Miami all week—and they don't like it. The musicians are returning to their rooms to watch TV or booze. Muscle Shoals isn’t any swinging town either, but at least they can count on playing there.

These five— drummer Roger Hawkins, lead guitarist Eddie Hinton, guitarist Jimmy Johnson, organist Barry Beckett and bass David Hood— are versed in the art of recording with Aretha. They’ve played every one of her sessions since her first gold record, "I Never Loved A Man," was cut in Muscle Shoals, January 24, 1967.

Aretha hasn’t gone back to Muscle Shoals since — because of bad memories from her first visit when her then-husband, Ted White, reportedly had a disagreement with an imported musician— and so Muscle Shoals musicians have travelled from Memphis to New York and now to Miami. These days Aretha calls the shots. And it's not hard to understand why.

Aretha has cut 12 singles and seven albums for Atlantic Records—the company that made her a legend— and almost all have reached gold disc status. Blistering ballads like "Ain't No Way," the dynamic "Since You’ve Been Gone," the funky blues of" I Never Loved a Man," galloping gospel of "I Say a Little Prayer," joyous love in "A Natural Woman." She can take anyone's song and make it sound better than the original.

All Aretha had going was talent and dedication, and after a decade of seamy side-street nightclubs and a string of unqualified record producers, she finally got there. She became the third biggest selling artist in rock 'n ’roll history— surpassed only by the Beatles and Elvis Presley.

But if the price of getting there was high, the price of being there was greater. Aretha, a sensitive young woman, found the demands and discords of stardom a heavy load to bear. Sometimes the weight was overpowering.

Aretha's marriage fell apart and ended in divorce. Her husband also acted as her personal manager and, after the separation, he maintained a fairly hefty percentage of her career.

There were several occasions when Aretha failed to show at heavily promoted concerts. Two producers are in the courts over no-shows. Two magazines published sensational stories which hurt her deeply and, 18 months ago, she decided not to do any more interviews.

This has been an especially tough year for Aretha. In May she was charged with careless driving in her home town of Detroit, and in July she was also found guilty of disorderly conduct. A report in the Detroit Free Press stated Aretha had run into a parked car. Police said that on their arrival, Aretha was belligerent and refused to co-operate. At the station, they said, she cursed officers and then, when she left in her white Cadillac, she bowled over a six-foot Parking Police Cars Only sign.

Aretha reportedly had just checked herself out of hospital where she was being treated for nervous exhaustion. She had been under medical care for six months and had announced her intention of cancelling public appearances for the rest of the year.

In addition, Aretha's father. Reverend C. L. Franklin, was charged with possession of marijuana in May. He was later acquitted. Franklin was also investigated by the Michigan State Attorney's Office over his International Afro Musical and Cultural Festival. The investigation centred around the soliciting of funds without the necessary registration.

Franklin had claimed the support of Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Nancy Wilson, Lena Horne, Berry Gordy, Bill Cosby and James Brown— many of whom later denied any knowledge of the federation. The investigation was dropped when the project was abandoned.

The entire situation preyed upon Aretha's mind, to the detriment of her career. This has been the least successful of her three years at the top, mainly because of a lack of recording sessions and bad publicity about concert non-appearances.

But Aretha has been showing signs of recovery. The fact that she's missed a few nights now seems incidental . . . Aretha did appear in the studio on several evenings, and she recorded a complete album during her Miami stay. And it turned out to be an occasion that few present would ever forget.

Saturday evening, the musicians are again gathered drinking Coke and dreading the sound of the phone. Around 8:30 it rings. A songwriter in California. She wants Dowd to hear a song she's written especially for Aretha.

Dowd stops her after the first lyric line: When I saw you with another woman. ‘‘No,’ he says flatly, “Aretha doesn’t like to do songs like that anymore.” As he puts the phone down, a black Cadillac rolls into the studio parking lot. The balding white chauffeur opens the rear door. Two young coloured girls step out, followed by Aretha in a navy blue pantsuit.

The musicians cheer softly and head for the studio. Aretha goes straight in and seats herself at the piano.

Surprisingly, she doesn’t enter the control room —where Dowd, Wexler and arranger Arif Mardin are— until eight hours later, just as she is about to return to her hotel. Aretha has been followed into the studio by an assortment of people, all Negroes. There is her brother, Reverend Cecil Franklin, and his mod wife, Aretha's four-member vocal backing group the Sweethearts of Soul, a male friend, a singer named Betty Wright and the elderly, white-haired J. W. Alexander, who used to manage Sam Cooke and Lou Rawls.

Wexler, who has been ill for several days, saunters into the studio and sits down beside Aretha, who by now has ordered several cups of coffee and is chain-smoking Kools. "What are we going to do tonight, Aretha?”

”I think I’d like to start with 'This Girl's In Love With You.'"

“Great,” says Wexler, and the musicians begin tuning up.

Wexler returns to the control room to direct operations while Dowd stands back to listen as Aretha sings the song through, accompanying herself on piano. Occasionally she stops to explain a vocal part to the Sweethearts of Soul.

Forty minutes later, the shape of the song is reaching superb proportions. Aretha is looking happy, cracking jokes with her girls, occasionally soul-slapping the outstretched hands. Unlike the girls, Aretha is wearing her hair natural.

Wexler suggests that a first take of the instrumental track might be in order. Aretha agrees, and her girls file off into a booth away from the musicians. Dowd holds up a pencil for silence. Aretha leans over the keyboard.

Her left hand plonks down into a bluesy chord and the song is rolling. The girls whisper “Baby, baby” and the band follows Aretha's punching fingers and stamping foot. The track is clear and the musicians dovetailing. The first take sounds perfect.

But Aretha isn’t happy. She doesn't like one of the girls' parts and there are a couple of other riffs she wants to work in on piano. Two takes later, Aretha is satisfied. Wexler agrees. The musicians file out to the coffee machine, and the engineer sets up a microphone.

The tape is rolled back and Aretha— chewing gum and smoking—takes her place at the mike.

Click. The tape is rolling and Aretha's voice is being electronically etched. “See this girl, this girl’s in love with you, ooh- oooo-ooh,” You’ve forgotten about Herb Alpert's original version.

Aretha is off, plunging through her bittersweet four octaves of ecstasy. “Said I need you, baby,” she cries.

The end approaches and Aretha writhes into gospel devotion; the engineer slowly squeezes the volume into silence. How he is able to do it, I have no idea.

It must be 20 seconds before anyone utters a sound. Aretha turns around and looks into the control room just as Dowd says: "Chriiiist, I don't believe it.” Neither does anyone else. Everybody has been shattered emotionally.

Aretha returns to the piano, lights another cigarette and starts to discuss her next song with Wexler.

The musicians return. Drummer Hawkins says to nobody in particular: “I love her. I love working with Aretha. The only time I don't like it is when we come here and she doesn't show and we have to go back and hang around at the motel. But when she gets here, it's just fantastic.”

The rest of the evening is equally eventful. Aretha cuts a stinging version of Dusty Springfield’s "Son of a Preacher Man," ad-libbing: “Hallelujah for the son. Hallelujah, oh-oh-oh, hallelujah for the son, he's the only boy. Oh Hallelujah.” It rings with the joyful wails of the tiny wayside churches in the South where people sing for their souls.

Aretha's life has been laced with sorrow. She was born in a coloured neighbourhood in Memphis and her mother deserted when Aretha was 6. Mrs. Franklin died four years later. Friends say this left a deep scar upon a child who was already shy and withdrawn.

She sang her first solo in church at 12, and toured with her father’s gospel caravan until she reached 18 when she decided to enter the pop arena. She signed with a record company which spent six years adamantly recording her with everything but the right material.

Nothing happened until early 1967 when Aretha moved to Atlantic Records and her career lifted into orbit. But her troubles were far from over. Her marriage floundered, although as friends later observed, “she never lost any of the deep regard she had for her husband, even in the toughest times.” But she did drink heavily for a time.

As Wexler puts it: “Every drink, every piece of bread, each piece of ground she walked upon, made her what she is. It all contributes and the more it affected her life, the more it must affect her singing.”

Aretha probably has no more ardent fan than Wexler, a man who is usually sparing in his praise. “She is uniquely a genius. She brings more to her sessions, contributes more to her records than any other artist. In that respect, she is at least as good as Ray Charles, whom I was also fortunate enough to produce.” Wexler would love to produce Charles and Aretha together on an album. Ray has agreed, and all that remains is for Aretha to consent.

Aside from Charles, Aretha has often been compared with both Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday, comparisons which Wexler feels are impossible.

“Both Bessie and Billie were one of a kind, just as Aretha is. Billie was completely into jazz, a different thing. She didn’t have Aretha's voice, but she had incredible phrasing. Bessie was church, more of a blues singer, but I don't think you can compare her with Aretha.

“One thing I do believe. There is no one alive today who can get within miles of Aretha, and that includes Mahalia Jackson.”

Wexler‘s working relationship with Aretha is a close one, and his respect and admiration for her talent are obvious. But this is not a usual studio arrangement, where producer tells the artist what to do and how.

Early in their association, Wexler would play a song he liked for Aretha and she’d accept or reject it. Now, if she is attracted by a tune, she takes it home and works on it. When she arrives at the studio, she has a concise idea of what she wants. She knows what bass line will sound best in the bridge, what the girl vocal parts will wind up like and how the drums should correspond to the rhythm. She is an outstanding musician herself, and as Dowd observes: “She’s like two different people in the studio: one is the musician playing the piano, the other is a completely independent singer. The two are not really closely related, except in their brilliance.”

It is now after 4 a.m. and dawn is approaching as the temperature resumes its flirtation with the high 80s. Aretha has just completed her first vocal take on "Son of a Preacher Man." She is restless and keeps throwing an earring into the air and catching it.

“I loved that first chorus, ‘Retha,” Wexlers’ voice cuts through the intercom. Aretha slowly turns. “I don't like the last part,” she says flatly. “Lets’ cancel it— no, let me hear it once more.” She decides that aside from one small section, it is all right and she then overdubs the offending part.

She picks up her handbag, a copy of Coretta King's" My Life with Martin Luther King Jr.", walks into the control room and asks to hear all the tracks. There is "End of the Street," "You Keep Me Hangin On," "Putting On" (written by Aretha's sister, Carolyn), "The Moment" and "Anyone Who Had a Heart."

Wexler introduces us and tells Aretha that I would like to talk to her briefly. She agrees (but no photographs) and we move into a small office. She has always been extremely shy, and there are times during our half-hour interview when I can’t help but notice that Aretha is shaking.

Q. Aretha, you are looking well, and I suppose I can presume you are happy with progress here?

A. Well, I wasn't feeling too well when I arrived tonight. I was sick in the stomach, but it went away once we got into the session.

Q. Is recording your favourite occupation?

A. Hmmm, yes, I would say it's my most enjoyable thing, other than being on the stage or just sitting around at home.

Q. But you're not doing any more concerts this year?

A. No, I’m taking time out to recuperate fully. I have no idea what we I’ll do next year, but I think we will get to England in February. I was supposed to have gone there in September.

Q. It's been said here tonight that you’re singing better than any time in the past two years. Would you agree?

A: I wouldn‘t say that long. I’ve had a pretty bad cold most of this year and I haven t’ felt too good. But you're right— I’ve been feeling it really good down here tonight.

Q. Let’s talk about some of the songs you’ve been recording here, and why you chose them.

A. I’ve always liked the song "Eleanor Rigby," and I loved the Beatles' version and Ray Charles' version. And I liked it well enough to want to sing it myself. So, we just started working on it. We worked out the arrangement in Detroit before coming down to Miami—we being the girls, my guitarist and myself.

I heard Percy Sledge sing "Dark End of the Street" and I thought the melody was very pretty. And the message— I liked what was being said.

"This Girls’ In Love With You" is not the sort of song normally associated with me, but it was similar to the stuff I was doing years ago for Columbia. I just decided to take another shot at it.

I like the music changes in "You Keep Me Hangin' On.." We worked on "Son of a Preacher Man" for quite a while in Detroit.

Q. It so obvious that your piano playing has a lot to do with the great instrumental tracks on your records. The entire rhythm track is built around your piano. I was wondering how you get the ideas for your left hand?

Hmmm, it's just the way I hear what I'm putting down. It's what I feel the musicians should follow me by. It's really only my interpretation of what I am.

Q. Yet it doesn't seem to be any effort to you—you launch into them without apparent strain.

It's just blood, sweat and tears.

Q. You appear to have a great deal of communication with the Muscle Shoals musicians.

Well, apart from working in the studio, we’re very good friends. I understand them, and they understand me. I love working with them.

Q. Which artists have influenced you in both your singing and piano playing?

Sam Cooke, Clara Ward, Oscar Peterson. That’s about it.

Q. What artists do you personally like?

Oh, there’s just so many of them. The Beatles, definitely the Beatles. I like Steppenwolf. Blood, Sweat & Tears are tough. I love B. B. King.

Q. What do you think of Janis Joplin?

- She’s nice.

Q. Your sister Irma told me recently that she can’t stand Janis.

Really. Wow. God, I wonder why?

Q. Irma said she didn't like critics having the gall to compare you with Janis.

Well, that’s my favourite little sister, fighting for me.

Q. What do you think of The Supremes?

I like them, and we’re friends. All of the Motown acts are my good friends.

Q. What has success meant to you?

It's meant security. Security in the sense that I’m doing for myself and not being dependent on my family. It’s given me that. It's also given me the enjoyment of recording and being on the stage and different things that happen—the good things—and the gold records and new clothes and the trophies and all those beautiful things. Plus, it's given me a sense of accomplishment.

Q. You say success has brought you independence from your family. Are you close to your family?

I wouldn’t get away from them. I couldn't. I guess they’re proud of me.

Q. What do you do with your money?

A. Mostly I put it back into my act, in gowns.

Q. Even though you say that success has brought security, I think many people identify with the insecurity of your style. When you sing a lost-love number, it seems as though you’re really into what you’re saying; you understand the insecurity.

I guess one takes away from the other.

Q. I understand that you did some work with Martin Luther King. How do you feel the racial scene is developing?

A. I think that’s too important a question to answer right off the bat. I’ll have to think about that one. Ask me again in a year.

Q. Are you optimistic about improvement?

I could say many things about that. In the sense that yes, it has improved, but there are other things I’d like to add, but I don't feel that I should go into it right now.

Q. Aretha, how do you spend an average day at home in Detroit?

Well I sleep all day, that’s the average. If I’m not working, I’m sleeping or rehearsing. I watch a lot of TV—all my soap operas every day. I watch all of them.

Q. Your three children live with you in Detroit?

Yes, they all live at home and go to school in Detroit. They’re just fine, and I’m growing older.

Q. Have you ever thought of moving to another city where the weather isn’t so inclement as Detroit?

A. Well, I do like Miami and I like California, but Detroit is my home. It is like fads that come and go. Just because you have the money you don't leap up and just leave your home.

Just as I can’t buy a mini if it doesn't look good on me, you have to be careful to make the right decision. I have to wear what looks good on me.

Q. When you were on the road, didn't you find the travel and so on something of a drag?

No, It's okay. We had it worked out so that I’d be two weeks on the road and two weeks off each month. It was a pretty good equilibrium. Plus, I don't have the sort of problems on the road that, say, the Beatles would have.

Q. Do you have any hobbies?

Yes, I like swimming. I play a little golf, and I do some cooking. That’s about it.

Q. What musical directions do you intend to take in the future?

Well, we had to venture into the jazz field with Soul '69. It was just a diversion from what we had been doing. I’m happy with the way things have been going generally. The next LP after the one we're working on now will be a gospel album—traditional and new gospel songs. I love gospel music; I still like to go to church and sing.

Q. Which of your hits do you like most?

"Respect." Definitely "Respect."

Q. Do you have any ambitions?

Films. I have no plans yet but we’ve had some offers, and I’m very interested.

Q. Do you think you’ll record in Miami again?

Yes, I like the sound and the atmosphere here. It's very nice.

Q. And will you continue to work out arrangements in Detroit prior to your sessions, so that you can just walk into the studio here and whip out the songs so effortlessly?

Well, we do like to have things together before we go to a session. But it all depends on whether we’re in a good mood when we’re working things out . . . if we’re really ready to get down to business. It's all circumstantial.

Q. When do you think you’ll resume touring and TV appearances?

Probably by the middle of January. I really enjoy stage work immensely, when I'm not broken down and tired as I am now.

Q. Yet on the surface, you don't look broken down or tired.

Well, why don't we just say I’m young and vibrant.

And she laughs very loudly. She s’ a ripe old 27.

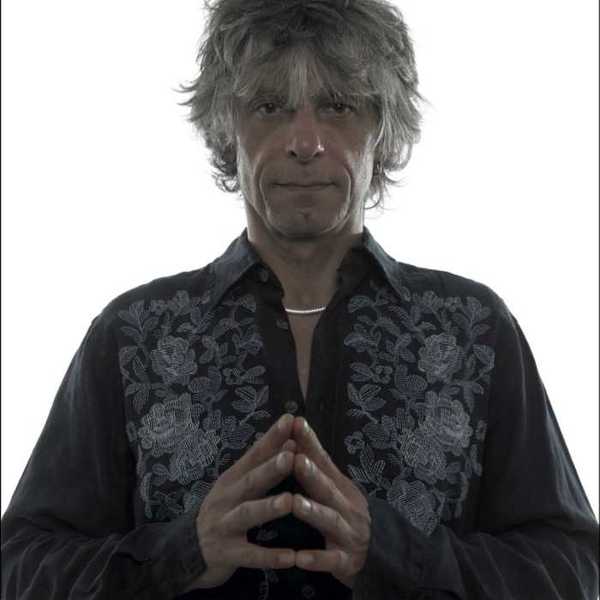

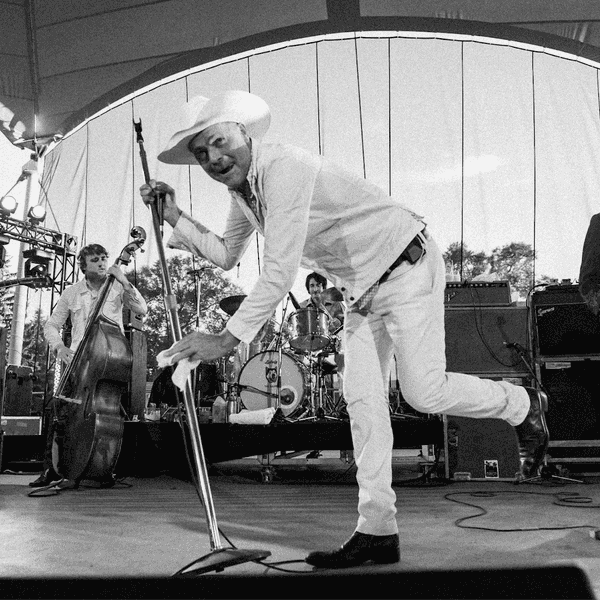

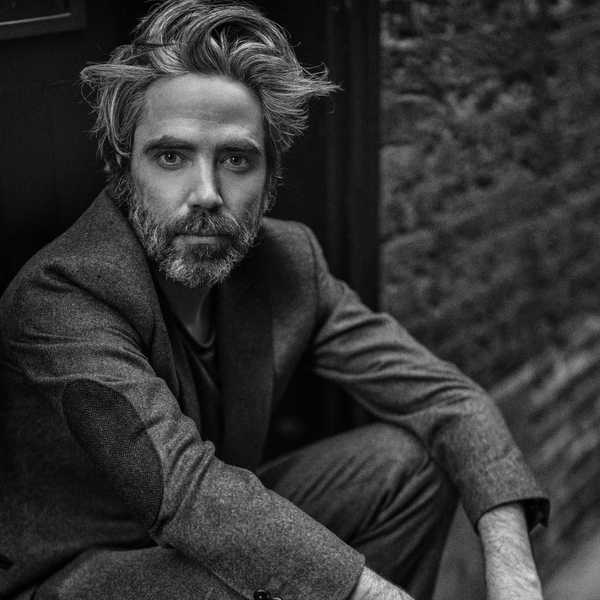

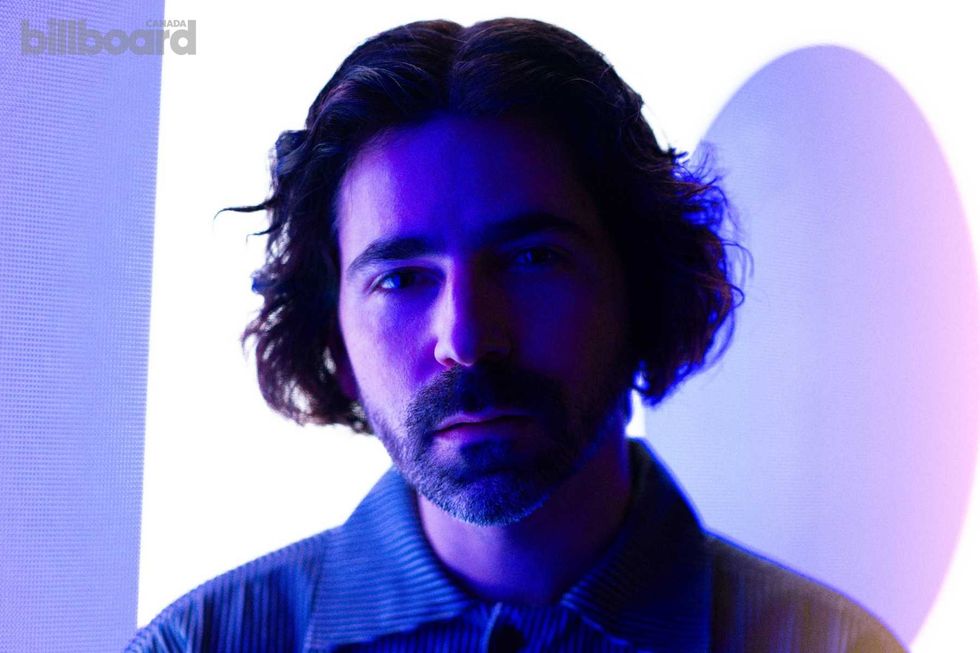

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026. Lane Dorsey

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026. Lane Dorsey  Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026.Lane Dorsey

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026.Lane Dorsey