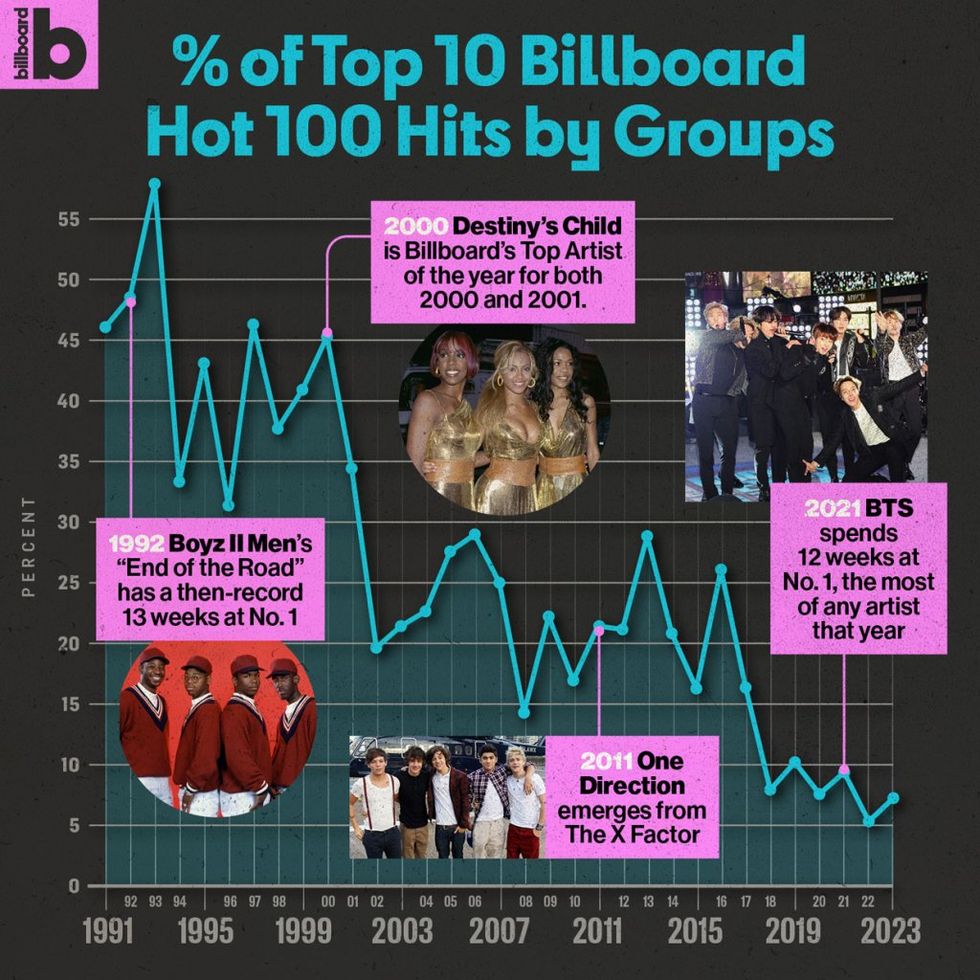

Groups Used to Rule the Hot 100 — Now They’re Endangered on the Chart

No groups appear anywhere on the latest Hot 100, and the number of groups with top 10 hits has fallen drastically over the last three decades.

Boyz II Men spent 17 weeks at No. 1 on the Hot 100 in 1994. But today, groups are few and far between on the singles chart.

Roughly 30 years ago, Boyz II Men seduced and cajoled their way to the top of the Billboard Hot 100 with “I’ll Make Love to You.” They enjoyed the view from No. 1 for 14 weeks — tying a record at the time — before dethroning themselves with another soaring, imploring ballad, “On Bended Knee.” In 1994, it wasn’t unusual for a vocal quartet like Boyz II Men to top the Hot 100, or get close to it; roughly a third of all top 10 hits that year were the work of R&B groups, rock bands, or ensembles in other configurations.

“When I grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, there was a constant barrage of groups,” says Michael Paran, a manager whose clients include Jodeci, a quartet that vied with Boyz II Men on the charts. R&B-influenced pop groups like the Spice Girls and the Backstreet Boys dominated the late 1990s. But the barrage started to let up in the 2000s, according to an analysis of top 10 hits between 1991 and 2023. Solo artists like Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake — who got his start in a group before striking out on his own — set a new standard for pop stardom, while rappers like Eminem and Nelly helped hip-hop reach commercial peaks that suddenly seemed out of reach for most rock bands.

And on today’s Hot 100, groups are an endangered species: Since 2018, groups account for less than 8% of all top 10 singles. The last ensemble to summit the chart was Glass Animals with “Heat Waves” in March 2022. No group scored a top 10 hit as a lead artist in the first half of 2024, and there is not a single group anywhere on the latest Hot 100.

There are many reasons for the demise of groups. The decline of rock, a historically group-focused genre, as a commercial force on the Hot 100 has certainly played a big part. But perhaps more important, advances in music technology have given artists in all genres the ability to conjure the sound of any instrument they desire without the need for collaborators. And social media, a key aspect of modern promotion, tends to reward individual efforts rather than collective enterprise. “Social media is about your voice,” says Ray Daniels, a manager and former major-label A&R. “Not y’all’s voice.”

In addition, aspiring artists have a better understanding of the financial realities of groups, which are costly to develop and then split any profits multiple ways. And labels aren’t matchmaking groups the way they did decades ago.

“I’ve been in bands, put the bands together, got the record deals, done the whole thing,” says Jonathan Daniel, co-founder of Crush Music, a management company with a roster that includes both major groups (Weezer) and star soloists (Miley Cyrus). “Trust me, if I was a kid now, I would never be in a group — I would be solo all the way. I wouldn’t need these other guys.”

Groups always used to have a practical purpose: Making a tuneful racket was considerably easier with the help of collaborators playing other instruments or belting harmonies. “Historically you often needed a group to make money — it was almost harder to be a solo artist,” Daniels explains. “You had to have people get together and play the music.”

This has not been the case for some time now. GarageBand hit Mac computers in 2004. Online sites like BeatStars allow vocalists to rent fully formed instrumentals. Artists can make beats and record vocals on their phone. “One guy can go in there and make himself sound like a group if he needs to,” Paran notes.

This can make artists’ lives considerably breezier, because they don’t have to spend time persuading — or arguing with, or massaging the egos of — group members who probably have their own views on songwriting and production. “It’s just much easier to have your own say than to have group members opining on what they want,” says Bill Diggins, longtime manager of TLC.

At the same time that technology has largely nixed the need for musical collaborators, executives believe that the prominence of X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, TikTok and other similar platforms further elevates individuals over groups. “How often are groups doing content together on TikTok?” asks Joey Arbagey, another former A&R who worked with Fifth Harmony, among others.

Even bandmates or singers who are in a group probably work to stoke their own social media presence — which represents a safety net if the group falls apart. “Every artist is focused on building their own numbers,” Arbagey continues. “That kind of destroyed that feeling of creating together.”

And those artists that still want to create with others are often aware of the financial implications of this decision: If they hit it big together, they don’t make nearly as much as if they hit it big alone. “When we were kids, we saw The Rolling Stones and thought, ‘They’re rich, they have a plane,” says Daniel from Crush. “We didn’t go, ‘Well, they have to split all the money five ways, but Elton John doesn’t.'” Today, however, thanks to the internet, “artists are much more cognizant of all facets of the music industry,” Diggins says.

On the flip side of that, when labels get involved, groups are also more expensive for them to support. “It’s cheaper to be in the business of a solo artist than it is to be in the business of moving multiple people around and styling and marketing multiple people,” says Tab Nkhereanye, a songwriter and senior vp of A&R at BMG.

The heyday of groups also coincided with a time when labels had much more sway over what music was popular — largely because anyone with aspirations to be heard outside their region needed the labels’ deep pockets and close relationships with radio and television. Record companies scouted for talent, helped put groups together, found songs for them to cut, and then pushed them out through dominant mainstream channels. “It was kind of a machine,” Paran says.

Today, however, U.S. labels aren’t typically involved with artists in the early stages of their careers when they might once have been shunted into a group. Instead, the record company often shows up after acts have already proven their ability to attract a devoted audience, typically through a combination of social media — which, again, caters to individual personalities — and streaming. And on top of that, the influence of traditional outlets like radio and television, which served as the launching pad for so many groups in the past, has nosedived.

Chris Anokute, a longtime A&R turned manager, points out that “most of the breakout boy bands and girl groups of the last 10 years came from TV shows like The X Factor — One Direction, Fifth Harmony.” “I don’t know if you can break acts like that if mainstream platforms like TV or radio don’t really move the needle in the same way,” he continues. “Everybody was watching when those groups went on TV 10 or 15 years ago,” Arbagey agrees. “Now nobody has cable.”

There is at least one country where music-based TV shows still drive listening behavior: South Korea continues to pump out groups at a steady clip, and BTS has made nine appearances in the top 10 on the Hot 100 since 2018. (Still, it’s notable that HYBE — the company behind BTS — and Geffen Records are attempting to develop a new girl group in the U.S. via a Netflix series, rather than network television.) In addition, the recent eruption of the catch-all genre Regional Mexican has propelled new ensembles onto the Hot 100, including Eslabon Armado and Grupo Frontera.

And while groups aren’t peppering the Hot 100 with major singles the way they used to, they maintain a prominent presence in another corner of the industry. “The one place that groups still hold a hell of a lot of water is the live experience,” Daniel notes. In the U.S. in the first half of 2024, U2 had the top tour by a wide margin, according to Billboard Boxscore, and Depeche Mode and the Eagles appeared in the top 10 as well.

While those are all veterans, more recent groups like The 1975 and Fall Out Boy also made it into the top 50. The presence of ensembles on this chart makes sense: On tour, even most solo acts bring backup bands or other musicians to help them bring their songs to life. Musical wunderkinds are few and far between, and crowds aren’t always interested in watching a lone performer sing or rap over a backing track for two hours, so group performance is still common.

But on the upper reaches of Hot 100, the closest thing to a group is usually a collaboration between two or three high-flying solo acts. “When you don’t see it, then you don’t want to be it,” Nkhereanye says of groups. “These days, it’s sexier to be a solo artist.”