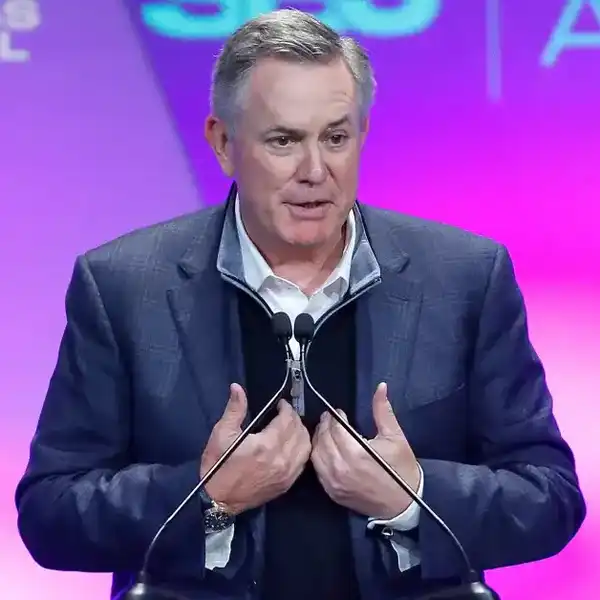

By David Farrell

What Was Said

The evolution of broadcasting in Canada

Let me begin by describing a bit about the evolution of the cable TV industry in Canada. It is useful to start there to set the stage for the changes we as regulators have enacted in response.

Canada’s television system has always been open to foreign content. Although the CRTC’s mandate is to ensure that our domestic broadcasting and production industries are reflective of Canadian culture, our system has always welcomed content from beyond our borders.

Major American television networks have always been available in Canada—initially as over-the-air signals and later as part of the TV packages of cable and satellite providers.

As the cable industry evolved, Canadians enjoyed access to a wide range of domestic specialty channels as well as to hundreds of television channels from around the world. These sources provide a multiplicity of content in English, French and many other languages besides including several in Mandarin. A breadth of programming such as this allows for a diversity of ideas and opinions, including both domestic and foreign-based news and information programming.

It goes without saying, of course, that among these foreign services, those of one nation dominate.

One of our main responses to mitigate such outside influence and ensure we could sustain domestic content and services was to regulate. The approach worked. It helped to fund and promote Canadian productions, and to ensure a vibrant and productive domestic market and gave virtually all Canadians access to this content.

A new challenge appeared in our broadcasting sector when major players in the cable business began to consolidate. Larger companies acquired smaller ones. This was largely in response to the competitive environment, with the introduction of satellite TV and later Internet Protocol television (IPTV), and to achieve more efficient operations.

Over time, television service providers became fewer and fewer in number, and larger and larger in size, although there are still a number of smaller independent players. Regulating in a way that takes into consideration their reality and that of the larger players is another challenge.

The market’s next step was to consolidate further in response to stagnating advertising revenues. Companies began making deals to gather production, programming and distribution services all under the same corporate umbrella. This trend toward vertical integration was not unique to Canada, but it did have specific impacts on us due, in part, to our relationship with the U.S.

We at the CRTC were concerned about the likely effects of such consolidation. We worried that it created the potential for programming and distribution services to become proprietary, for previously widely available content – both Canadian and non-Canadian – to be split along corporate lines, and, in extremis, for the broadcasting system to fail to meet its public-policy objectives as a result.

Around the same time, it became evident that the TV-watching behaviours of Canadians were beginning to change. They were starting to access more and more online video over the Internet and on their mobile devices. A new trend was emerging.

We now know some of the outcomes of this early shift. Where those digital media services were in their infancy ten years ago, and were complementary to conventional broadcasting models, they are anything but nascent players today. They are popular, successful and ubiquitous.

Data published in the 2019 edition of the CRTC’s Communications Monitoring Report provides a Canadian perspective on such trends. It shows an increase in total revenues for online television services of nearly 44% from 2017 to 2018; and an increase in estimated revenues for online audio services of nearly 17%. More is, I’m sure, to come. Disney and Apple recently launched new streaming services in Canada. Both will undoubtedly capture audience eyes and dollars.

All of this is not to say the market for conventional broadcast services is heading off a cliff. Such services—and particularly those that provide news and information, and which allow Canadians to tell their stories—remain of great cultural importance to Canadians. Again, I will point to data from our 2019 Communications Monitoring Report. In 2018, the average Canadian aged 18 or older watched a little more than 26 hours of traditional television per week, and about three hours of online content. Radio numbers are similar. Adult Canadians listened to about 15 hours of programming a week on conventional radio stations, and a little more than eight per week online.

How do we regulators respond to this trend? We change. We must. Because the frameworks we at the CRTC have implemented since our inception in 1968, based on our legislation, are not flexible enough to adapt to the current environment. Created more than a half-century ago, our regulatory tools are not well-suited to respond to the change being wrought by digital media.

Our regulatory responses

As I indicated a moment ago, our initial response to regulating the flow of foreign content into our broadcasting sector was to regulate. Canada, as you know, shares a huge border with our neighbour to the south—a neighbour who also happens to be the world’s largest exporter of English-language cultural products.

And although we share many cultural, economic and social similarities with the United States, we are fiercely proud of the differences that set us apart from them. Canada is a nation that embraces two official languages—English and French—and cultures, that celebrate a young and vibrant population of Indigenous Peoples, and that prizes multiculturalism.

The mandate entrusted to the CRTC under Canada’s Broadcasting Act is to ensure that Canada’s broadcasting system protects this unique cultural identity in the face of foreign influences—not only those from the United States, but also from those dozens of international services I referenced previously.

How did we do so? Through regulation. To use an analogy, we created a wall around our broadcasting industry. We allowed only approved services to penetrate into the garden beyond that wall and created conditions for our domestic broadcasting and production industries to grow and thrive.

Let me explain four tools in particular that we used. The first: mandatory Canadian ownership and control over Canadian broadcasting entities. The second: the requirement that broadcasters obtain a licence from the CRTC. The third: quotas that mandated a certain percentage of content that is aired be Canadian. And the fourth: a requirement that traditional services invest money back into the production of Canadian content, including news and information programming.

This approach helped to bring high-quality Canadian information and entertainment programming to Canadians that reflected their reality. It enabled the launch of the first Indigenous TV channel in the world.

Our approach worked well. It sowed seeds. It nurtured growth. It allowed Canada’s content system to flourish for nearly 40 years. But it was not immune to change. The walls surrounding our garden could not stand unchanged forever.

One of the first new regulatory challenges we faced occurred when the trend toward vertical integration emerged in the broadcasting market. At the time, we judged that such a trend could have a negative impact on the sector’s ability to meet its public-policy objectives. We responded by issuing a new framework for such integrated companies that allowed them to respond to new market opportunities, while also establishing measures that prevented them from harming their competitors or restricting consumer choice.

For instance, we put in place rules and codes to ensure that:

programming services make their content available to their competitors on a fair and non-discriminatory basis

negotiations between distributors and programming services are conducted in good faith and Canadians do not lose access to their television services during such negotiations, and

independent distributors and broadcasters are treated fairly by the large integrated companies.

This framework has evolved over the years through a series of policies and decisions, for the benefit of all Canadian viewers.

Modernizing our approaches

We began to ask profound questions about the future of our broadcasting system—and the suitability of our regulatory tools—when digital media’s influence became undeniable. When evidence showed that more and more Canadians were turning to online video over the Internet and on their mobile devices versus conventional viewing.

We launched a comprehensive review of our television framework in 2013 as a result. In its form, this review was intended to be a study of our television framework in light of the inescapable presence and influence of digital services. It was much more than that, however. It was, I’m confident in saying, a watershed moment for public policy the CRTC conducted consultations with industry stakeholders and the public at large.

The CRTC is an administrative tribunal that acts in the public interest. The decisions we make are therefore based on the public record. The more that record contains a diversity of public input and a multiplicity of views, the better informed we are to make decisions that benefit the public interest.

As a result, and during our review, we provided Canadians and stakeholders with new ways to share their opinions with us: Internet discussion forums, real-time commentary during formal Commission proceedings, video submissions, and more. The result was a broader, deeper and more fulsome public record, which was fundamental to the decisions that flowed from it.

From a policy perspective, the decisions that stemmed from this review changed the way we regulated the broadcasting system.

We provided for greater flexibility on those broadcasting quotas I referred to earlier.

We mandated broadcasters offer more flexible television viewing packages to consumers. These included an entry-level service package of stations that was designed to be not only affordable but also include local and regional television stations that provide news and information programming.

We also mandated broadcasters to allow consumers to build on that skinny basic package by selecting only those discrete channels they wanted to view.

Finally, we created a Television Service Provider Code that set out the rights of consumers in their interactions with the cable and satellite companies.

The review also created significant outcomes for industry. One of these was a wholesale code that established certain parameters around the commercial arrangements between programming and distribution undertakings—with a view to curbing those disputes that inevitably occur in an increasingly competitive marketplace.

We at the CRTC are often called upon to resolve disputes among programmers and distributors. It’s part of the work we perform. In all cases, we aim to resolve such disputes through informal means and using the expertise of our experienced staff. In the event that this approach does not work, parties can ask for a staff-assisted mediation process whereby we meet confidentially with all parties to see if they can agree to a mutually acceptable solution.

Should informal resolution or staff-assisted mediation be unsuccessful, parties can choose final-offer arbitration, through which a panel of our Commissioners will review both parties’ final offers and select one in a binding determination. This process is reserved exclusively for monetary disputes.

One important thing to note about our dispute-resolution process is that it enacts what we call a “stand-still rule.” This means that when a dispute arises over a service, for example, the disputing parties must continue to offer their services, and distributors must continue to distribute them, at the same rates and under the same conditions as prior to the dispute. This rule applies until such time as the Commission issues a decision.

I’m pleased to say that we have been able to resolve most disputes through early staff assistance or staff-assisted mediation. If anyone would like to learn more about the process, I would be happy to provide further information.

Harnessing Change

All of this brings me to today when digital media’s influence over conventional broadcasting is undeniable and irreversible. When those prescriptive rules that we regulators depended on for so many years appear less well suited to adapt to the pace and scope of change created by the Internet.

Don’t get me wrong. From a consumer perspective, these are happy times. Content has never been more abundant and diversified, nor of a greater quality. This is a positive development.

Yet for us regulators, abundance creates challenges. How can we at the CRTC continue to deliver on our mandate to preserve and promote Canadian programming in a sea of content and platforms? How can we ensure that local and regional productions – which are dearly valued by Canadians – are not compromised by such abundance? How can we respond?

Two years ago, the Government of Canada asked the CRTC to study the future of programming distribution in Canada, and the extent to which this future environment may support a vibrant domestic market. Our Harnessing Change report, which we released in May 2018, was the product of that exercise.

In preparing our report, we considered whether it would be feasible to maintain our current approach, deregulate the traditional players, or apply the existing regulatory approach to the digital world. We found that these options were unsustainable and would result in harm to the current system, content creators and Canadians.

Its conclusion: the current regime is becoming less and less effective. The economics of producing Canadian content are such that it needs financial support. Without this support, Canadians could lose the diversity of content they currently enjoy, as well as access to certain types of content that are more expensive to produce, such as news and drama. This scenario runs contrary to Canada’s public policy objectives.

Clearly, new approaches are needed for a new era.

Our report proposes future policy approaches to support the production and promotion of audio and video content made by Canadians. These include:

focusing on producing and promoting content made by Canadians that can be discovered and enjoyed here at home and around the world

recognizing that everyone who benefits from Canada’s broadcasting system should contribute to it, and

creating regulatory and legislative tools that can quickly and easily respond to sweeping changes in technology and consumer demand.

These principles would help drive the system toward the goals of ensuring Canadian content is well funded and discoverable—on traditional as well as digital platforms. They would also ensure that support is maintained for local news programming, French-language content, content for Indigenous Peoples, and other public-interest priorities. In other words, those very priorities described in Canada’s Broadcasting Act.

Whatever approach the Canadian government ultimately adopts, one thing is certain: government intervention is necessary to ensure Canadians continue to have access to the content they care about, including news programming and the unique stories that reflect who they are.

We live in challenging times. But with challenge comes opportunity.

Conclusion

The approaches that the CRTC took to ensure a strong and vibrant Canadian broadcasting industry worked well for a generation, but they are now under strain. The walls surrounding our garden are no longer thick enough, tall enough or strong enough to withstand the change brought by digital technology.

The opportunity before each of us now is to adapt our respective systems to harness such change, and use it to realize greater opportunities for content creators and distributors. I believe Canada is on the right path to doing so. Our approach is comprehensive, forward-looking and adaptable.

We are in regular discussions with our regulatory peers in the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications, the International Institute for Communications and others. We discuss common challenges and learn from each other’s best practices and approaches.

I look forward to hearing more about the particular approaches being used or being contemplated here in Taiwan. We have as much to learn from you all here today.

We all face similar challenges, and I daresay none of us has a comprehensive list of solutions. Sharing information helps us all harness the change before us.

— CRTC Chair Ian Scott to the Cable TV Summit of the National Communications Commission in Taipei City, Taiwan, Thursday, Nov. 28

New CRTC data on Canada’s broadcasting system

The following is the Broadcasting Overview contained in the newly released CRTC Communications Monitoring Report

In 2018, broadcasting services generated total revenues of $17.1 billion, a 1.2% decrease compared to 2017, and contributed approximately $3.5 billion (20% of total revenues) to Canadian radio and television content through their respective funding mechanisms. Out of the $3,016 million made in Canadian programming expenditures, expenditures on news grew by 5% from 2017 to 2018, reaching $737 million or almost a quarter of the total CPE expenditures. (See the Television section for more details)

BDUs generated almost half of 2018 total broadcasting revenues, reporting $8.4 billion (49%). Television services followed with $6.9 billion (40%), and radio stations generated $1.8 billion (11%).

In comparison, Internet-based audio and video services were estimated to have generated revenues of $4.8 billion in Canada, approximately 28% of the revenues of the traditional broadcasting services.

Link directly to figure 4.1 Distribution of total broadcasting revenues ($ billions), 2018 (Total = $17.1 B)

In 2018, television distribution via cable continued to generate the most revenues at $4.5 billion and reported strong profitability with an EBITDA of 15.0%. In regard to television services, discretionary services generated the most revenues at $4.0 billion and reported a PBIT of 23.5%. In fact, except for private conventional television stations (which collectively reported a -8.8% PBIT), all categories of broadcasting services were profitable in 2018.

That being noted, most services saw their revenues decline. Only CBC/SRC radio, CBC/SRC conventional television stations, and IPTV showed growth in their revenues. The increase in revenues of CBC/SRC radio, up $32 million (10.9%) compared to 2017, and CBC/SRC television, up $119 million (12.6%) compared to 2017, may be, in part, a result of an increase in parliamentary appropriations and an increase in television national advertisement sales resulting from the sports coverage of the 2018 Winter Olympics.

The majority of radio revenues came from commercial services (82%), which include both AM and FM radio stations broadcasting in French, English and third languages. Radio revenues have been declining; however, on average 83% of Canadians still use traditional radio each month.

As is consistent with previous years, the majority of television revenues came from discretionary services (58%), which relied on subscriber revenues to generate most (66%) of their revenues.

Finally, among BDUs, IPTV still leads in terms of growth, reporting revenue growth of 4.5% from 2017 to 2018, while DTH services are still the most profitable distribution services, reporting a 27.4% EBITDA in 2018.

In terms of the regional distribution of revenues, the most populous provinces, Ontario and Quebec, lead with 38% and 26% of broadcasting revenues in 2018 respectively, while according to the 2016 Census

In 2018, as in previous years, the broadcasting industry was largely dominated by a few entities. Together, the top 5 entities generated approximately 81% of total broadcasting revenues. Entities operating radio stations, conventional television stations, discretionary or on-demand services and BDUs generated 64% of broadcasting revenues in 2018. Entities operating only one type of these services accounted for 6% of total broadcasting revenues.

CCS Contributions

In 2018, broadcasters contributed a total of $3.479 billion towards Canadian content. CPE represented the vast majority (87%) of those contributions, followed by BDU contributions (12%) and CCD contributions (1%).

Canadian broadcasters also support Canadian content in a variety of other ways, such as through the exhibition of Canadian content, copyright and other programming expenditures, and the production of Canadian radio programming.

Even though total broadcasting revenues have declined from 2017 to 2018, contributions to Canadian content have increased by 2.3%. In, fact, contributions to Canadian content have increased in the past ten years, by an average of 2.4% per year.

Although total broadcasting revenues have declined since 2015, total contributions to Canadian content have remained stable over the same period. In fact, they have varied in the $3.4 and $3.5 billion range since 2014. Contributions to Canadian content growth is measured at 2.4% on average, per year for the past ten years.

Only radio CCD contributions display negative growth, having declined by 1.7% per year for the past ten years. These contributions represent 1.3% of all contributions to Canadian content for the past three years.

Television CPE increased by 2.5% per year for the past ten years, from $2.4 billion in 2009 to $3 billion in 2018. Over the same ten-year period, there has been an average decrease in contributions per year from CBC/SRC conventional television services (-1.3%), other (public and not-for-profit) conventional television (-3.8%), and on-demand services (-5.4%). There has, however, been an average increase in contributions per year from private conventional television (1.2%) and discretionary services (5.5%).

Although BDUs contributed to the LPIF (now defunct) and the ILNF, the majority of these contributions over the past ten years have been directed to local expression, Certified Independent Production funds and to the CMF (95% of BDU contributions, in 2018).

Internet-based audio and television services estimated revenues

Internet-based audio and television services, also known as over-the-top (OTT) services, are provided through Internet access. These services, according to the research firm Ovum, generated estimated revenues of $4.8 billion in Canada in 2018, comparable to the 2018 cable revenues ($4.5 billion). These revenues compare to roughly one-third of the traditional, regulated broadcasting revenues.

Internet-based video estimated growth is still on the rise, compared to last year, as revenues grew by an estimated 43.8%. The majority of estimated revenues from Internet-based video content come from subscription-based video-on-demand (SVOD) services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and Crave TV.

For Internet-based audio, streaming is the method of accessing content that generates the most estimated revenues. The estimated growth for Internet-based audio services revenues, while significant at 16.6%, are less noteworthy than the average annual growth rate of 20.7% for the past 5 years.

SVOD refers to subscription-based video-on-demand service. This is an Internet-based service model in which a client pays a subscription fee to gain access to a library of content. This category includes services that air the content of the library according to a linear schedule (e.g., Sportsnet Now) and services that permit a user to choose from a catalogue of content that is available at any time (e.g., Netflix, Crave and Club Illico).

TVOD refers to transactional video-on-demand service. This is an Internet-based service model in which a client pays for specific content but generally does not pay to access the service itself (e.g., iTunes, Microsoft Movies & TV, and the PlayStation Network).

AVOD refers to advertising video-on-demand service. This is an Internet-based service model in which a client typically has free access to content but is exposed to advertisements (e.g., YouTube).

Although Internet-based services are becoming more popular, a great majority of Canadians continue to use traditional television and radio services. In 2018, on average, 80% of Canadians watched traditional television on any given week and 83% listened to traditional radio in any given month. These penetration figures are far higher than those for their Internet-based counterparts, which stood at 56% for Canadians watching Internet-based television services and 63% for Canadians streaming music content on YouTube.

Additional information concerning Internet-based audio and video services as well as the methodology is provided in the Radio and Television sections of this report.