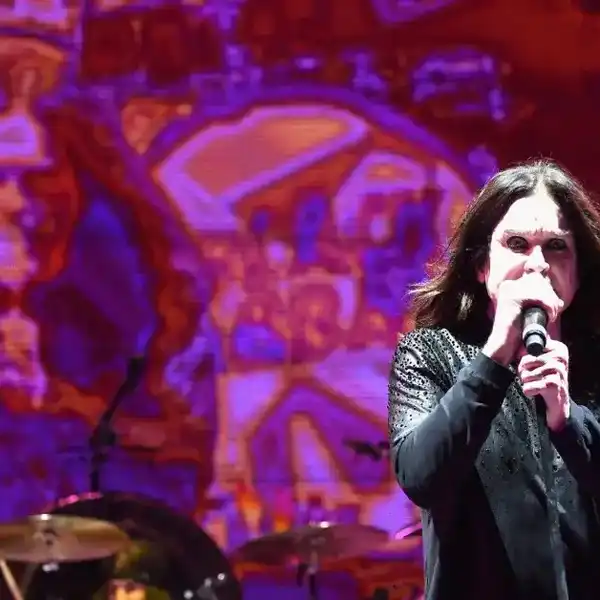

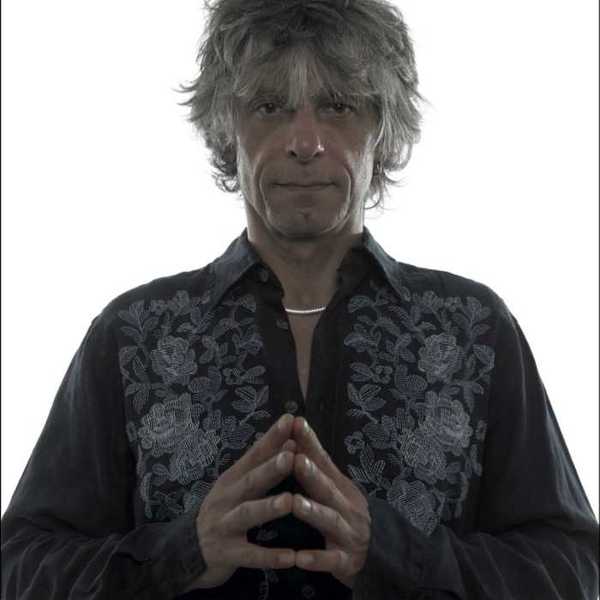

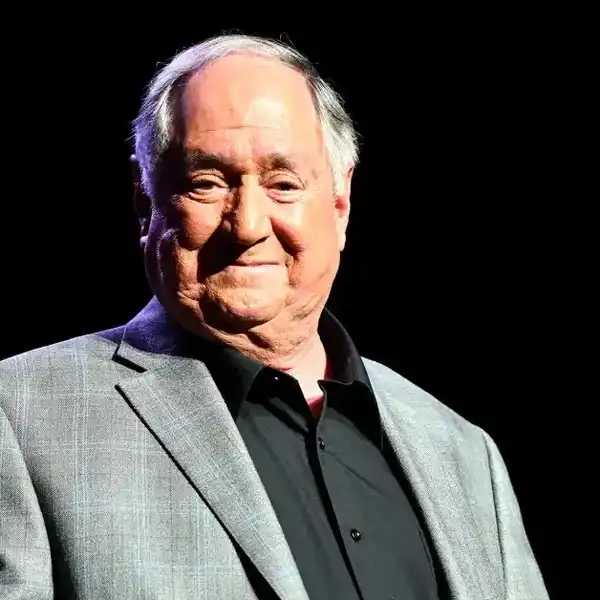

A Conversation With... Richard Thompson

The English folk-rock pioneer is back with a new album, 13 Rivers. In this revealing interview, he discusses that record, his creative cycle, love of analogue, soundtrack work, protest songs, and more.

By Bill King

The press release for Richard Thompson's new album 13 Rivers reads: A return to New West Records, the 13-song set is the Grammy-nominated artist’s first self-produced album in over a decade and was recorded 100% analogue in just ten days.

It was engineered by Clay Blair (The War on Drugs) and features Thompson’s regular accompanists Michael Jerome (drums, percussion), Taras Prodaniuk (bass), and Bobby Eichorn (guitar).

13 Rivers is a bare-bones, emotionally direct album that speaks from the heart with no filters.

“There are 13 songs on the record, and each one is like a river,” Thompson explains. “Some flow faster than others. Some follow a slow and winding current. They all culminate on this one body of work.”

A high-water mark in an overwhelmingly impressive career, 13 Rivers was recorded at the famed Boulevard Recording Studio in Los Angeles. Previously known as The Production Workshop, which was owned by Liberace and his manager, the locale served as the site for seminal classics by Steely Dan, Fleetwood Mac, Ringo Starr, and hosted the mixing sessions for Pink Floyd’s legendary The Wall.

Of the album, Thompson says, “The songs are a surprise in a good way. They came to me as a surprise in a dark time. They reflected my emotions in an oblique manner that I’ll never truly understand. It’s as if they’d been channelled from somewhere else. You find deeper meaning in the best records as time goes on."

I was able to corner Thompson recently for a brief chat.

Bill King: You are playing my home area Louisville, Kentucky. Have you played there before?

Richard Thompson: Yes, I have. It’s a fairly regular stop. I have a base of support there and play Lexington as well. I think there is a kind of thriving music scene in Louisville. It seems to be a bit of a hub for musicians these days. The woman opening shows right now, Joan Shelley, is from Louisville and part of that musical community.

B.K: It was always like that – even in the 40s’, 50s’ and 60s’. You had so many great jazz musicians: Lionel Hampton, singer Arthur Prysock, drummer Horace Arnold, trumpeter Jonah Jones from the area that made the city a vibrant scene for music. A lot of history near the banks of the Ohio River. You recently moved to New Jersey.

R.T: I did. It’s an accessible place to live – handy and a short distance from New York City - a short hop from U.S. airports to the U.K. It’s very convenient.

B.K: Thirteen Rivers – what’s the thought behind the new recording or inspiration?

R.T: I wrote all of these songs in a short space of time in about six months, and it was clearly time to do an electric album. I went into the studio with some of the troops and recorded. It’s so much a cycle process. Every two or three years I seem to have enough material for a band album and, in between those times, I have material for other projects – acoustic and the like. It’s just part of the cycle.

If you write songs within a compressed period, they do have a commonality to them. Sometimes, music ideas overlap, and sometimes, lyric ideas overlap. I do feel each song belongs to the other and probably a couple of other songs I didn’t feel that strongly about are not on the album. It’s a process where you edit and eliminate what seems to be the more random elements from song selection.

B.K: You recorded at the Producer’s Workshop. Working in a room with so much history – do you get a sense of history like others have recording in Sun Studios or Soulsville, U.S.A?

R.T: That’s a nice idea, but actually, it was just cheap. It’s a really good studio. It’s been neglected the last thirty years or so and only coming back into being a studio and used regularly. For a while, Pink Floyd was there; Steely Dan was there – it was owned by Liberace bizarrely enough. The number one thing is, it’s a good sounding room, and we were able to record analogue there as well – a great advantage for me. It gives it a much warmer sound - generally speaking. There is a difference, especially with bass and drums. For me, it’s about how things blend and getting a cohesive sound – a more three-dimensional sound. Some people say I get crazy with this depending on the generation you grew up with. A twenty-year-old would say they can’t tell the difference – digital is fine with them. It’s a very close thing, but I claim I can hear a difference.

B.K: There is warmth, and the instruments seem to breathe between each other.

R.T: I think in that case it’s coming across and I'm glad you can hear that as well. I think the thing that is missing from music is that random element. It didn’t use to be possible to painstakingly fix audio recordings. When there were mistakes you had to leave them. I think that was part of the charm of it. You can stick anything in Pro Tools and clean it up. You don’t even have to perform that well in the first place to produce a good sounding record. With so much control you did certain kinds of randomness that gave charm to some older recording techniques.

B.K: Your guitar sound is lovely. Do you have a particular studio set-up?

R.T: Most of the time you go into the studio, plug into an amp and off you go. It’s probably a less crucial part of the process. There are mic techniques for recording electric guitar and acoustic guitars and not that many choices. It’s one of the most straight-ahead components to making a record.

B.K: Is the guitar a constant in your hands?

R.T: Not right now. If you’ve been holding a long time, it’s good not to hold it a long time and give your muscles a rest. I play the guitar several hours a day, and sometimes I take a day off. I will take three days off to give my body a chance to heal. If you have a go at it relentlessly, you tend to get tendinitis and all kinds of other problems.

B.K: Do you still get a rush playing live?

R.T: I think it’s the best thing in the world. It’s the best reward for a musician to play in front of an audience – no question! It’s that feeling where you kind of give something of yourself and play from the heart, and it reaches other people’s hearts. To me, that’s the best feeling there is. That sense something has been communicated.

B.K: 1000 Years of Popular Music 1068 – 2001 – how long did it take to assemble?

R.T: There were various incarnations of that show. Every time we toured, we’d change the repertoire. There was a lot of research involved that was a lot of fun. I kept coming across extraordinary things from the musical past especially in the pre-recorded era. It took a few months before taking it on the road and learning the material. Every couple of years we take it out again, and I have to do the whole process over. It was a real education for me.

There are only so many possible things said in lyrics. It’s always been love songs and sometimes social unrest. There are story songs, ballads, that talk about local murders and other local dramas – nothing changes. You’ve got 1000 years, and we are still singing about the same things.

B.K: One on my favourite documentary soundtracks is Grizzly Man, one you did with director Werner Herzog. Are there more to come?

R.T: I did one recently that’s going to be on HBO next year called The Cold Blue – footage of World War ll in colour that was shot by William Wyler. He shot for a film released in 1943 -1944, a documentary, The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress. There’s other footage he shot that has never been seen – another twenty hours of film. The documentary assembles that footage and is full of stories about the pilots and crew of the Eighth Air Force. It’s remarkable footage. A lot is shot over Germany under fire. Some of it is quite distressing and narrated by eight survivors all in their nineties. That was a lot of fun to do especially working with a chamber orchestra.

B.K: The planet in ways is under siege from the far right – do you ever feel the need to write possibly a protest song or words that push back?

R.T: If I write protest songs at this point, they are fairly subtle. There comes a time when you write a song that tells it like it is that doesn’t hide anything. You write a song demanding physical change. There are certainly times when that happens, the Vietnam War for instance. Perhaps we are heading to that time again. We shall see!