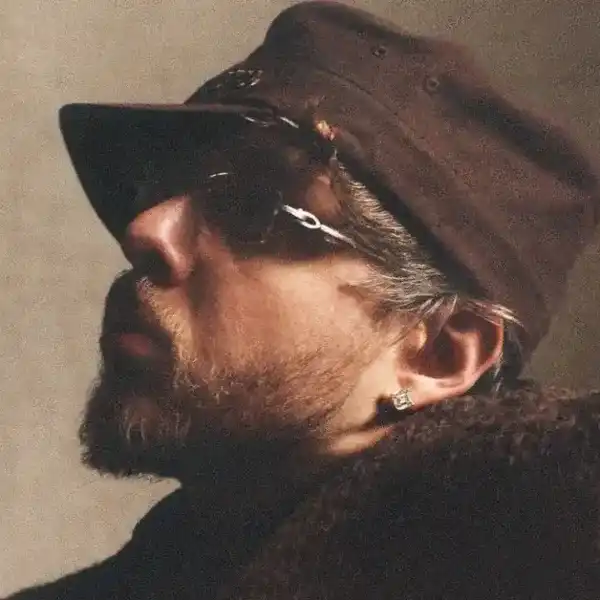

A Conversation with...Warren Cosford

One of the glorious pleasures of writing for FYI is the people I get to speak to. My mom’s side of the family is roots Italians who immigrated and passed through Ellis Island in the last century.

By Bill King

One of the glorious pleasures of writing for FYI is the people I get to speak to. My mom’s side of the family is roots Italians who immigrated and passed through Ellis Island in the last century. To be in their company was like standing in the middle of mid-town traffic. You didn’t just jockey to get a word in – you shouted over everyone and engaged anyone within sight. Thus, talking is not an issue. Listening took practice.

I read Warren’s daily blasts with greater interest than the Lefsetz Newsletter – not because the writing isn’t of interest but more so to do with Warren’s fierce political rants and passionate love of music.

Back forty years ago we were shocked to hear the U.S. was backing murderous regimes in Guatemala, Chile, El Salvador and the CIA was assassinating world leaders. The Soviet Union was stockpiling a nuclear arsenal that scared the shit out of us. Last week it was revealed the American right lied its way into a war with Afghanistan – lied about its accomplishments and slow results. The story fell flat. Thousands have died as they did when political and military hacks prolonged the War in Vietnam. No wonder folks now believe their own facts – mostly borrowed from Facebook and partisan news outlets. Kudos to Warren. Warren trims the fat and posts what matters.

Months back we talked and that conversation lasted one hour and fifteen minutes – 18 pages! For the moment, I’ve trimmed it to a few milestones in the celebrated man’s career and those exchanges rock!

Bill King: Where does this passion for radio come? I know as a young person you sang in a choir at CBC, but how did radio become your life’s work?

Warren Cosford: I think it had a lot to do with the times. I'm from Winnipeg as you probably know, and at the time Winnipeg became the rock and roll capital of Canada. Of course, we did not know that at the time, but, we were. And one of the reasons for that is we had two great rock and roll stations in Winnipeg: CKY and CKRC, and they were in heavy competition against one another. They were very visible because, in Winnipeg, if you talk to anybody in the music industry, they'll tell you that one of the reasons we became the rock and roll capital of Canada was the community club system.

In every community in Winnipeg, there was a building that had a place to play cards, chess, checkers, ping pong. They had a dance hall, they had a hockey rink, baseball diamonds -whatever. It was a place for kids to hang out. That’s where a lot of bands were formed, and that's where the bands were able to play. Rock and roll became part of our lives because not only did we hear it on the radio, we were part of it in these community clubs.

I wanted to be in a band. It probably was what I wanted to do most of all until I brought out a set of drums – Slingerland drums that were used drums and I got into a band as many people I knew did, but I was a terrible drummer. I didn't realize how bad I was until I saw the drummer with Al & the Silvertones that later became the Guess Who, so I thought I'd better find something else to do. Fortunately, I had a leg up on radio because I got into it when I was ten. I got into CBC radio as the kid on many many CBC radio dramas through the 60s, and that gave me a leg up to get into the business. The man that gave me my first part-time job was Cliff Gardner.

I worked with a lot of announcers over the years Bill, but Cliff Gardner was the best all-around on-air performer that I ever worked with, and he was the guy that gave me my first chance in radio – an excellent position to be in. Instead of being in a band, I ended up playing records around town.

The station I worked for was CJOB, an MOR station, which meant it got all the records. The station didn't care about them so I could keep them all. That got me got rolling in radio. However, I still hadn’t figured out what I wanted to do in radio, so I became a disc jockey, I became an operator and then one day I went into the studio - the production room and saw they had these big 350 machines. I saw this guy operate this machine by remote control. He was producing a commercial, and I thought you know what, I think that's what I want to do, and that's what I ended up doing.

B.K: Great cultural shifts were occurring across continents and music was on the frontlines. This would have been before the Beatles - Elvis era, I’m guessing?

W.C: Oh, way, way before the Beatles.

The first 45 rpm I ever bought was The Lord Made a Woman. I forget the guys' name but it was a rockabilly kind of song. We had these dances all over the city; again at all the community clubs. The radio stations were a big part of those community clubs. The disc jockeys would make an appearance, play some records and say hi to the kids. I remember one of the big things in 1958, there was a song called My True Love on the radio - I thought it was an excellent record. I bought the album, and in the liner notes, it said that Jack Scott was a Canadian, from Windsor Ontario, and I thought 'wow, you can be a Canadian and be in rock and roll and succeed', and that was it for me.

About a year later, there was this kid from Thunder Bay named Bobby Curtola, and he had a radio hit and came to Winnipeg, opening for Bob Hope of all people at the Winnipeg Arena. Before he went to the arena to perform he went over to the Clifton Community Club which was our community club. He went on stage and lip-synced Hand and Hand With You, and that was a massive inspiration to all of us that wanted to be in this business in one way or the other.

Bobby Curtola had a hit record, and it was made at a radio station in Port Arthur, Ontario. All of a sudden, everybody wanted to get a record made at a radio station, and lots of them did.

I’m sure you know from the history of it all, that the Guess Who, or what became the Guess Who, were adopted by CKY in Winnipeg, particularly Burton Cummings. He used to call the radio station regularly. Harry Taylor at CKRC chose— Neil Young and a band called The Squires. There was this competition between the radio stations as to who they could record and put on the radio. And it was huge.

B.K: I don’t know if that kind of relationship between artist and radio exists anymore. Much more arms-length?

W.C: It was enormous. When I came to Toronto to work on radio in 1970, the mantra was about the Canadian content regulations. I thought, “What the hell are they talking about?” I don't know what percentage Cancon was at CKY or CKRZ and didn’t know if it was thirty percent. All I know is in Winnipeg we had lots of bands on the radio. They were being charted and celebrated.

B.K: It took some convincing to get radio open up and become more inclusive of Canadian artists. Were you there?

W.C: Yeah, I was at CHUM at the time and I didn't understand the thirty percent in Canadian content regulations. I thought that was way too high. I was the production manager at that time at the station 1971 when all of that was happening and I remember J. Robert Wood called me and said, “Well, we got these Canadian content regulations we have to do. Apparently, there are a whole bunch of records out there radio won't play because they're Canadian. Let's all see if we can find some of them.”

I had quite a collection of records since I used to get them all. I would kind of figure out myself what I thought were the hits. They weren't always the records that ended up on the radio, but one of the recordings I loved a lot that I knew was Cancon because the guy sending in the record a few months earlier had a hit, was R. Dean Taylor. I didn’t know where the hell he was from or anything, but I knew that he was on the Motown label. I had this record called Gotta See Jane, I thought was fabulous, but I never heard it on the radio. I brought it into Bob Wood and said, “This is Cancon. This is an excellent record, let's put it on the radio.” So we did. And that's how R. Dean Taylor on the Motown label with Gotta See Jane became CHUM’s first number one record of the Cancon era.

B.K: Didn’t he also have a hit with Indiana Wants Me?

W.C: He did. Indiana Wants Me was before that.

There was a real connection with Toronto because R. Dean Taylor ended up becoming part of what they called the “Clan” which was a group of people at Motown assigned the task of writing hit records for the Supremes after Holland Dozier and Holland left Motown. They were getting pissed off at being ripped off or at least that's what they thought was happening to them. Motown had to find someone to write songs for the Supremes and R. Dean Taylor was part of that group.

Meanwhile, here's a peculiar one for you. As you know, the top 40 stations in Toronto at that time had operators - people that were actually in the studio running the board playing the records, running the commercials and all of that. The two top 40 stations at that time at the end of the '60s were CKFH, a Foster Hewitt station, and, of course, CHUM.

There was this guy whose name was Don Gooch who was an operator in Toronto on radio for both CKFH and CHUM at the same time. When CHUM and CKFH found that out, they fired him. Fortunately, he and R. Dean Taylor were friends. He went off to Detroit with R. Dean Taylor and ended up becoming an engineer in Motown. If you listen to R. Dean Taylor’s record, Indiana Wants Me, you will hear a police officer at the end of the record with a bunch of sirens and whatnot as R. Dean Taylor is being captured by the police. The guy acting as the police officer on it, and mixing the record was Don Gooch from Toronto.

B.K: What was it you did that assisted in elevating CHUM-FM into that #1 position.

W.C: That was one of the most exciting times of my career because I had just finished as the production manager of the Evolution of Rock: The Music That Made the World Turn Round, a 64-hour documentary, and that was just fabulous. I was feeling burned out about it all so my wife and I went on holiday for a couple of weeks, and spent some time in Indianapolis with some friends I’d made because of the production of the documentary. I came back to Toronto and remember driving down the 401 from Kingston and turning on the radio because I knew that Q107 had signed on the air at some point when I was away. It was a great sounding radio station as expected because Allan Slaight was the owner of the radio station. People had always told me that Allan Slaight was the guy that made CHUM and that somewhere along the way, he and Allan Waters had a falling out. Slaight left CHUM, and CHUM was never quite the same.

I return after my holidays and arrive Monday morning when Bob Wood calls me into his office and says, “We need you to program CHUM FM.” I said, “What?” He said, “We need you to program CHUM FM.” I said, “What happened to Duff Roman?” He said, “Well, Duff has resigned, and there's something else he wants to do outside of radio. He's in some business with concerts and whatnot, and he's no longer the program director, and we need you.” I said, “Come on. I mean really. We’ve got great program directors in our company. We’ve got Chuck McCoy who is doing a hell of a job in Vancouver, and we have Paul Ski doing a hell of a job in Halifax. I think Rick Hallson was the program director at that time in Winnipeg and Bob - move one of those guys up because I’ve never programmed in my life.” He said, “That's fine. When you came to CHUM, you had never been a production manager at a top 40 station before, and you did ok. I’m counting on you to figure this out and do ok for us, and that's what we need you to do.” I then became the program director at CHUM FM.

I should say one thing about all of this that is significant because we're talking about going back to Winnipeg and getting involved in radio. What we created at CHUM in the early days, in the 70s and beginning actually in the late 60s when J. Robert Wood came to CHUM - between him and me, we created the Winnipeg mafia. What we did, and indeed, I did with operators, is I brought in people from Winnipeg who had never been operators at radio - they were production people but they were from Winnipeg. They were part of the Winnipeg music culture. I figured, what the hell, bring them to CHUM, bring people to CHUM, and be brave people and challenge them to be great ops at 1050 CHUM, and that's precisely what we did. There was a whole Winnipeg thing that was going on at CHUM at the time and the people there ended up calling it the Winnipeg mafia and they were absolutely a critical part of my and our success.

B.K: Jack Scott passed recently. What was your connection?

W.C: I remembered back in 1963 in Winnipeg, I was a big fan of this guy Jack Scott who was the first Canadian rock and roll singer I'd ever heard. He had all these hit records and seemed to always be on the radio in Winnipeg. He was my favourite singer. It was 1963 and I wasn't working in radio, although that was my goal, to work part-time at least and maybe over the summer. I’m listening to CKY, my favourite station, and there's a guy named Jerry Bright who is the jock on the radio, and he's doing this Battle of the New Sounds, where they would take two records, and they would battle it out. Which record is going to win? You had to call in with your favourite record to decide who's going to win.

I was an Army cadet and I just got home and turned Ed on the radio, and there’s Jerry Bright with Battle of the New Sounds and he's playing Jack Scott. And it's 1963. He's got Jack Scott up against Bobby Vinton or someone, and I think, wow, Jack Scott hasn't had a hit record in a long time. I’m gonna vote for Jack and I had my mom vote for Jack. My father voted for Jack. I had all my friends vote for Jack.

Jack Scott won.

It was a record called Laugh and the World Laughs With You. It won on Tuesday night, it won on Wednesday night and it won on Thursday night and it won on a Friday night and it became the pick of the week, and it was fabulous.

I thought isn't that interesting. Jack Scott Laugh the World Laughs With You eventually peaked at #6 on the CKY chart. It never was played on CKRC, the competition. As far as I know, it wasn't a hit record anywhere else but on CKY in Winnipeg 1963. Jack Scott had a hit record. He had one of those records I'd been thinking about that - the record companies for whatever reason was not a priority. They weren't trying to get the radio stations to play them. That record would have been lost if I hadn't done what I did. Now I’m programming CHUM FM and I'm thinking, I've got to find my Jack Scott.

At that time, I didn't have a lot to do with picking the music beyond sitting in the music meeting - listening to what people thought we should be doing. I got everybody involved. That's part of the culture of what I do when I manage radio stations. I get everyone interested in being involved in something like picking music - everybody comes in. Let's talk about music. Let's see what we can do and let's see what kind of fun we can have. What is the rotation going to be and all that kind of stuff?

I was in those meetings and it was just coming up to Christmas 1977 and I'd only been programming a few months. Benji Karsh said, “You know record guys don't know you,” because I wasn't interested in talking to the record guys - that's what Benji Karsh did. He said, “You really should talk to the record guys - they bring us promotions - the interviews or whatever else and they don't know you. Would you do that?”

I said, “Well, I'll tell you what, go to the record guys and tell them, just before Christmas to bring me the records they think should be on the radio and are not their priorities, because I'm looking for great records that for whatever reason, are not priorities.” He said, “Sure.”

One of the guys who came by was Graham Powers with CBS Records and Graham said, “I was talking to Benji, and he says you're a big fan of Phil Spector records or records that sound like Phil Spector records - the “wall of sound” and all of that. And he says you're a fan of some guy named Jack Scott.” I said, “That's true.” He said, “Well, I’ve got a record here that kind of sounds like Phil Spector might have produced it and it's called Bat Out Of Hell by some guy named Meat Loaf.” He said, “You might like it. You know, I’d like to give it to you see what you think,” and I said, “Fabulous.”

I saw a few more record guys and whatnot and picked up a few more albums and went into see J. Robert Wood and said, “This is what I'm doing over Christmas; listening to some music, and he said, “What have you got?”

He went through all of them and said, “Meat Loaf. - Bat Out Of Hell - you know, I read a note Lee Abrams sent to all the stations - don't play this Bat Out of Hell thing; the lead singer is fat, the music is loud, long guitar solos - you've got a bunch of stuff there that are not priorities and there's probably a reason why they're not priorities - good luck, have a nice time over Christmas and maybe you will find the kind of record you'd like. I went home over Christmas and put on Meat Loaf's Bat Out Of Hell.

Bill, it was like Holy fuck. This is incredible. This one cut, Paradise By The Dashboard Light. I mean that was a cluster buster. How could you not notice that record on the radio? I thought it was great.

After New Year's, I’m back at the office and put the album on my turntable in the office and turned it up loud and people start to come in. What the hell is that they asked? I said - the record is called Bat Out Of Hell. It's not a CBS record; it's on some little record label called Cleveland International Records. But listen to Paradise By The Dashboard Light. Everybody laughed about it of course because we're all about the same age, and we had those kinds of memories at the drive-in. I said look, let's have some fun with this, let’s really freak out Q 107 and Allan Slaight and everybody over there because they've been told not to play this record.

Let's put this record on heavy rotation for one week and see what happens. We'll choose three cuts - don't run in heavy rotation because at that time there was a limit to the number of times a record or a particular single, a cut could be played on the radio; the CRTC had put those regulations in place. To get in heavy rotation, we had to play at least three cuts. So we did, and the phone started ringing. I thought wow, this is fabulous, people seem to like this.

Some callers said, “What the hell is that shit too,” but mostly the phone calls we were getting were pretty positive. And then my phone rang and it was a guy named David Sonenberg and he introduced himself as the manager of Meat Loaf, and I felt like, fuck, I've never talked to a manager of a band before. This was great.

“How are you David?," I said. He says, “Thank you for playing the record like you're playing it.” David said he was talking to CBS and they're thrilled that we’re doing what we’re doing and hoped it spreads around the country. I said, “Well, as you know, David, CHUM FM is a P One station, which meant that we were considered by Radio & Records magazine in Los Angeles as being one of the most important radio stations in North America.

CHUM FM at the time was the only P One radio station in Canada that would report to Radio & Records. I said, “You know we're going to be showing them that we're playing the damn record, so maybe that will help you get something going there and I'm sure because we're playing it here in Canada other stations around Canada will likely play as well.” I also said, “By the way, we do these live broadcasts here in Toronto at a place called the El Mocambo. We had the Rolling Stones play there last June for the Love You Live album. Why don’t you see if you can get the money from CBS to come up to Toronto and play the El Mocambo?”

He said, “I will absolutely do that and I'll get back to you.” He got back to me and said, “We're going to be there.” I said, “Tell you what, why don't we do two shows – let’s blow everybody's mind.” And so that's how we did two shows at the El Mocambo. After the smoke cleared, CBS Records told me they sold 25,000 albums following the live broadcasts of Meat Loaf. at the El Mocambo. You know the record companies never lie. But that's what they told me, 25,000 albums, and said, “I think we’ve got a hit.” What that did for CHUM FM was - it said to record companies in the United States that Toronto could break records that most people weren't even playing.

B.K: Warren, I'm going to skip to Warren's Network. When did you start this?

W.C: I guess it was 1998 when I started that because with the computer thing it was clear something was going on with all of that. I had a friend in Windsor who was a bit of a geek. He worked at one of the auto companies and used to get all of these programs like Word and whatnot and rip them off. His son was a friend of my son. I asked what do you see happening with this? He said, I've got to tell you Warren, in the auto industries it's changed everything for us. It's fabulous. He said, if you're going to stay in radio, you should think about doing this.

At the time, I was consulting after Radio 4 Windsor, which is a whole other story. I thought, well, you know that's kind of cool. I'll go around and to my clients and I'll tell them all about the Internet and what we're doing with all of this and I can communicate with you - I'll kind of look like a cool guy being able to do all of that. I went out and I think it must have cost almost $2,000 for a desktop at that time. I got into it and said, you know, this is a great way to keep in touch with all my friends in the radio music business. That's how that started.

I called it Radio Pro at the time because that was my consulting company, and then 1999 came and I’m going through the Internet and it's starting to ramp up. While consulting I’d meet clients and talk about Meatloaf and talk about other bands that I was involved with or performers who were not record company priorities.

When I was in London with BX 93, a country station - we were among the first people anywhere to play Garth Brooks as an example. When our music director/program director added The Kentucky Headhunters, the Canadian record label didn't even know that they'd released it. In fact, they ask Ian McCallum, who was the PD, and me to come to Toronto to explain to their promotion people what the hell was going on with country music. We'd come out of the Urban Cowboy thing and country was getting back to being country again. There were a lot of new acts that were happening and Garth Brooks was one of them.

At any rate, I'm going around consulting and talking to people about looking for great records, the records that are not record company priorities because there is no reason that you should be playing the same records as your competition. This is what is going to make you different. I remember going back – I think it was one of the stations in Saskatchewan and the program director said, you know your Meat Loaf story was great. He said,” I thought I’d buy the book – Meat Loaf's’ biography is out.” I said, “Really. That’s fabulous, I didn't know that. I'll pick it up myself.” He said, “A funny thing about it, you tell this great story about how CHUM FM Toronto, Canada and you grew Meat Loaf in North America but according to the Meat Loaf’s book, you didn't. There's no mention of CHUM FM - no mention of Toronto. No mention of Warren Cosford, nothing.” I picked up the book and he was right.

For whatever reason, Meat Loaf., or his publisher, or the record company - whoever it was, neglected to mention any of that.

Of course, that was a huge story.

At that point I thought, you know, I've got to start writing my story or someone's gonna write it for me and I'm not going to be included, and, that’s how the list ramped up!.