A Conversation with Musician and Producer Lou Pomanti

Bill King sits down with the highly-decorated composer, producer and musician to talk about his work with Michael Bublé, Robyn Black, The Canadian Songwriters' Hall of Fame and more.

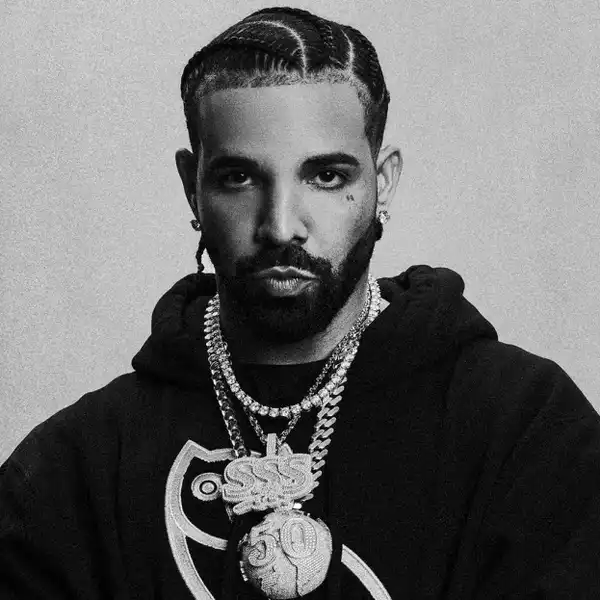

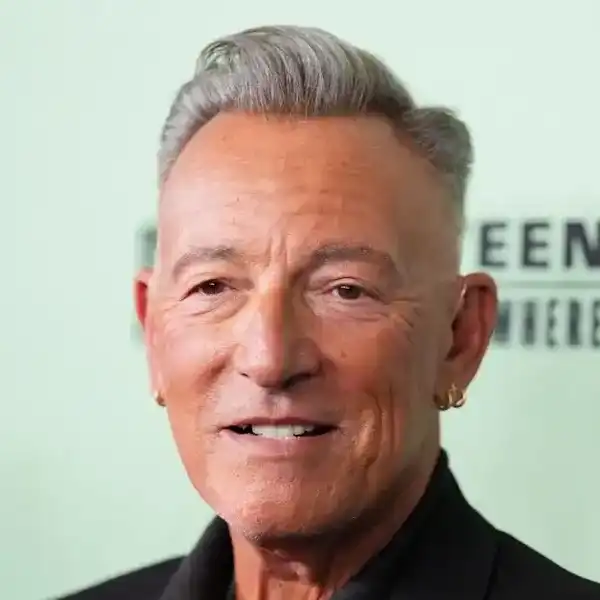

Lou Pomanti

In a career spanning multiple decades, Lou Pomanti, a distinguished composer, producer, and musician, has garnered acclaim as a Gemini Award winner with five nominations to his credit. His impressive portfolio includes contributions to various musical projects, encompassing scoring, songwriting, producing and performing for films and albums. Notable collaborations include famed acts such as Blood, Sweat & Tears, Platinum Blonde, Triumph, Jeff Healey, Kim Mitchell and an extended tenure with Michael Bublé, during which he played a pivotal role in producing and writing some of the artist's chart-topping hits.

Pomanti has been the Musical Director for The Juno Awards, The Genies, The Geminis and, for five consecutive years, The Canadian Songwriters' Hall Of Fame. His diverse and prolific journey through the music industry incorporates a rich concentration of talent and personal accomplishment.

I spoke to Pomanti at the Redwood Theatre in Toronto.

Welcome in, Lou. You know this room well.

Well, yes, I know this room and love this room. I had two or three Oakland Stroke shows here, one private and two public shows. I love it. My band is named after Tower of Power, who grew up in Oakland. There was a club in Oakland they played in when they were coming up, and they were nobodies. The way Mimi describes the Redwood is like this: with the distressed brick, it's a classic old building. It's over a hundred years old. It's got a vibe. I love it here.

You've worked with, recorded and produced many singers. What goes through your head? The singer comes to you and expects results. You can assess where the singer can go because of limitations, and then there's the potential for stretching and growth.

Take my solo album, which came out about a year and a half ago. It's called Lou Pomanti & Friends. I wanted to do a second solo album. So, what do I do? I do what I think I'm good at. And that is, I have my friends come in, my favourite singers that I know and guest with me, and I craft the arrangement and production around that singer and try to make them sound as good as possible. If you don't know the person and they come out of the blue, you have to listen and you have to find out what they're good at, find out what they're bad at. And you gotta 'accentuate the positive.' I try to wrap them in beautiful arrangements.

There are some singers who just want a piano. But then some singers want to put everything around them, the strings and the woodwinds and everybody.

When a singer comes to you fresh, they may bring along bad habits that must be eliminated to get to the core of their voice. This is where you play the role of a psychiatrist.

Well, as a producer, we're part psychiatrists, right?

In some manner, I look at each person differently. How you approach them, so they don't say, I'm out of here because this is what I do and who I am. Sometimes that's a struggle.

You work with lots of singers too. The most important thing I tell young them is that every project is different. There are the projects where, say, a female singer will come in, or a male singer, it doesn't matter, and you'll talk about the arrangement, and then they'll go away. I'll craft the entire track by myself without their input, they'll come in and sing for two hours, I'll get them to sing it eight or ten times, okay, see you later, and I send them the final master. Then there are the singers who want to be involved, are creative, and want to be there at every step of the process. And that's a whole different scene, as opposed to you just being hired to wrap them in beautiful wrapping paper, right?

Do you consider yourself an accompanist?

Oh, yeah. Even though I have solo records, I'm rarely at the forefront of the tracks. It's more like I'm trying to highlight the instrumentalist or the singer. I have had trumpeter Randy Brecker play on many of my tracks over the last three or four years. A mutual friend introduced him to me. Whether it's my solo stuff, Robyn Black or Marc Jordan, he's probably played on 12 tracks for me and wrapped them in a beautiful bow. He is one of my childhood idols and one of the greatest soloists ever. You just do your thing, Randy, and I'll wrap it for you.

I always thought the same thing because I frequently employed Mike Murley and William Sperandei – saxophone and trumpet, respectively – as my horn section. They are both unique players and beautiful soloists, and then I just got out of the way. I handled the arranging and the tracks. Sometimes, stepping outside of what we do, some players can go to places we can't or even think of.

That's why comping is such an important part of record production these days. When I worked with Robyn Black, Will, Mike, or Randy, it's like three or four tracks. They're all great. And then I let a day go by, and come back fresh and comp it. And I may use the first two lines from track one, the second two lines from track two because you're looking for gems. That's why a guy like Kevin Breit has had such a excellent session career. Because he's going to give you stuff you've never thought of. Some stuff you don't want, but that's okay because he will give you a little bit of magic that nobody else can give you. And that's what producers are looking for.

I spend long sessions on YouTube, traveling the world and watching pianists of every stripe. It's opened up this continuous flow of Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson, classical virtuosos, through an algorithm that keeps feeding you. Piano technique, hand placement, finger technique, harmonic advancement and score reading — lessons from the world's greatest tutors.

I've been a student at YouTube University since it started, but the most important thing that's happened to me with YouTube in the last eight years is that I've learned how to mix. I'm now a mixer. I mix all my own records. I mix all my solo records. I mix all of Robyn's records. I mixed the John Finley record. Mixing is daunting. For guys that came up when we came up, the engineers and the board were like, okay, you musicians, you stay away from that board. Now that's, that's way above your head.

We sat next to the engineer all the time, ready to pester and adjust a fader.

That's right. But don't share. Did I ever touch a knob at the 400 sessions I did at Manta? I wouldn't have dreamed of it. It was like a leap of faith, but it's all there on YouTube. And even though some engineers may be technically better at the technical aspects of mixing, how could he compete with my 50 years of musical experience? He can't. I will have a perspective on that mix that only someone who's been in the business and had the experiences I've had, which is only me, will bring to that record.

I've learned that maybe even though some of my mixes may have little too much 250 in that mix. I hope the mastering engineer will catch that and listen to the musicality of the mix. I've learned to trust myself and just go for it.

Do you move from headphones to speakers in your mixes?

What I do is I've got my main setup in my studio. I've got my speakers, and I have a sub. And then when I need to check things, I bought the Slate VSX system for headphones, which emulates different rooms in all over the world, different mixing rooms or in your car. That's my B-room check. The VSX phones. I can listen to Stephen Slate's room in L.A., or I can listen to Howie Weinberg's room in New York City or whatever. It beats running out to your car in the middle of winter and listening. You know, it's the best place to listen.

Where were you born here?

I was born in the northwest end of Toronto, in Weston at Weston Road and Sheppard. I was born in Little Italy at Keele and St. Clair, but we moved up to the west end when I was a couple of years old. I grew up there.

Were you dragged into the music thing?

Okay. It's funny. There is no musicality in my music in my extended family. None. Zero. There's a rumour about my uncle Guido singing with big bands, but nobody has a picture to back it up.

Did you perform the ancestry DNA analysis for the musician?

Yeah, I did. But no, there was no musicality at all. I've got two older sisters, and my father forced them to take piano lessons when they were young. They both took piano lessons for six years, ended up in grade three and could barely play, so they gave up. I was number three and discovered the piano in our basement, still there, given to us by my Aunt Rose.

I started plunking out notes myself when I was twelve years old, and my dad came up to me and says, "Do you want to take lessons?" I say, "No." He says, "I'll make you a deal." Take six lessons. If you want to quit, you can quit. I'll never mention it again." I say "okay, as long as I don't have to take classical." So I went to Rose Music Centre in downtown Weston, I was 12 years old, and they gave me an 18-year-old teacher and guess who it was? It was Glenn Morley.

That's major talent.

So, when I was 12, 18-year-old Glenn was my first music teacher. I did six months with Glenn and switched to the Royal Conservatory and studied classical for the next six years. And then I went to Humber.

I was practising six to eight hours a day throughout my teens. When I went to Humber College, I stopped going to the Royal Conservatory because one would say, 'black', one would say 'white.' I cut out the conservatory, which I'd had enough of anyway. Believe me, I'm no classical pianist.

But the thing is, to have a touch, those are the things you must develop.

Right, and the sight reading helps.

Did you advance composition and arranging skills at Humber?

I think when I started getting busy in the studio session scene in 1983, and 25, the thing that cemented it was they couldn't throw anything at me I couldn't sight read. I had been reading Debussy and Ravel and Mozart and Beethoven, even though I was playing them badly by classical standards, I could still read them. To get a part at a session for a jingle, a TV show, a record, or whatever.

One thing I loved as a kid was going to the library and borrowing the scores.

I never did that. I got the records, but I never got the scores until I was in college.

I'd listen to Beethoven symphonies as I followed the scores. Then Stravinsky and Shostakovich.

The only thing I couldn't understand with those classical dudes and still can’t is why they read a transposed score. Why don't they use a concert score? When I'm following along, I don't want to transpose the trumpet note. Or the bass clarinet note. I want to see what the pitch is. Not their pitch. I found that frustrating.

Is there an arranger who, in your opinion, who beautifully crafted the voicings for instruments such as violins, strings, and horns in such a way to cause you to research?

Johnny Mandel. Pete Rugulo. Ralph Burns.

Now that you're having fun with your band, Oakland Stroke, and considering your other projects like the Soul Revue, what's on your mind?

I'm 65 now. I decided in my late 50s that it was time to stop worrying about money. I had had a good enough career that money wasn't an issue. I've had no problem making my mortgage or anything like that. I didn't have to get up and work. I had spent a lifetime working on other people's music, playing sessions, whether it's jingles, records or TV shows, and writing jingles for 15 years. I was always the behind-the-scenes guy. By the time I was 55, I had little to hold up and say, 'So what have you done in your life?'

Where's the inventory?

You can listen to this record, but it's by a different artist. And this sold a lot of records. But it's not me; it's me contributing to this record. Right? So, I thought, let's see what you got. I started recording, which was very gratifying, and I got a lot of reaction — no money, of course, but positive feedback. So, the question becomes. How good am I? How good can I get? How good is my music when I compare it to my idols? Not to the surrounding people, but to the top level of what you aspired to as a kid, the Gino Vannellis or the Earth, Wind & Fires or all Herbies and Chick and all those guys, you know. How does it stand up, and it was hard.

I listened to this classical pianist Marc-Andre Hamelin and nine impossible piano pieces to play. I almost closed the lid of the piano and bid farewell.

That's what happened. I was a teenager who saw Oscar Peterson at the Ontario Place Forum. I would have this push and pull of, Oh my God, that's the most fantastic thing in the world. I love it. And the other side in my heart and soul, I will never play like that. It's elevating and-and depressing as a young kid.

The same happened to Oscar Peterson when his dad played him Art Tatum. But now you understand it's about finding your voice.

It's a great time in life. I get to indulge myself. Hey, listen to this — my poor wife. Hey honey, come on down and listen to this, right?

I won't even do that anymore.

It's great. It's great. I feel sorry for her.

It all began with that relationship with the keyboard, with the piano. What do you feel when playing solo piano, and alone?

When I was younger, I used to improvise on the piano all the time. I found it very free to not improvise to a tune; improvise from zero. Just the way Herbie and Chick used to do that. And I found it incredibly freeing. I don't do that anymore. Now, I'm looking at how to arrange a unique song.

When I do my jazz gigs now, there are two songs that I always do solo. I do "Lush Life," where I've worked up my arrangement. I also like "God Only Knows" by Brian Wilson, a masterpiece of a song. And I play them differently every time. So that's my outlet for solo piano right now.

What I would love to do is have an hour of solo piano. That's worked out with set arrangements I can improvise within. I think that would be a gas.

Do you have other projects on the go?

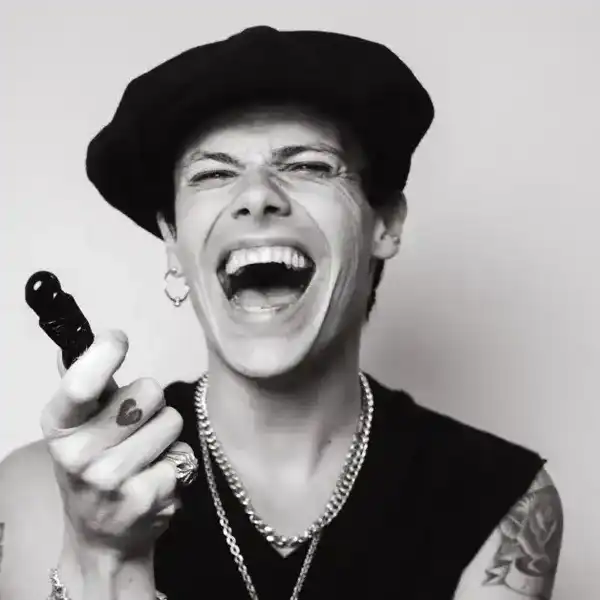

I just released a joint solo record with Robyn Black. It's Robyn Black and Lou Pomanti, and the album is called Butterfly. That's been a labour of love.

I finally met a singer that I don't charge a cent too. She's my collaborator. We write together. I find her voice uplifting. She gives me goosebumps every time, and she's one of those intuitive singers that I'm always amazed by. It's like, turn the mic on, shut up, and let her go, just like you said.

That's a special relationship to have with a singer.

I wish I had 20 years ago, but of course, she would have been 15, so that wouldn't work.

We've all worked with 15-, 16-, and 17-year-olds in our lifetime on exceptional projects. Other interests.

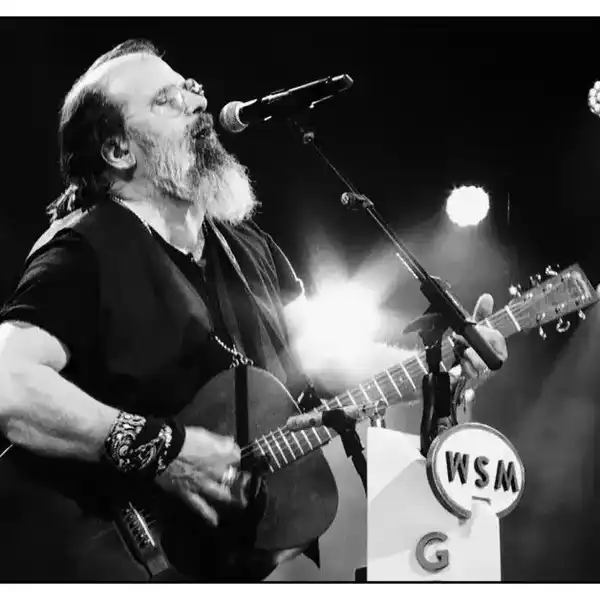

I've been doing a lot of sessions at the house. A lot of string and horn writing for artists worldwide. I just finished one in Prague and did an interesting project you'll be interested in. He's a smooth jazz artist out of Nashville. His name is Les Sabler. But that wasn't the exciting thing about it. He called me after I produced a few songs for him and says, "Would you mind putting together my book for me? My horn book is everywhere and needs someone to merge it and make it right." He says, "I'll send you the original scores, and you can make the book."

Well, he sends me the original scores and six of the tunes are by Jerry Hey. Okay. For all of you folks who do not know who Jerry Hey is. Jerry Hey is one of the best small band horn arrangers ever. From Sea Wind, everything from Michael Jackson's "Thriller" to everything.

See, if I had said no to that job. If I'd said, ah, I'm too busy, I don't care, I've never heard of the guy, I would have never possessed these six original Jerry Hey scores. I'm looking at these scores and learning more in an hour than any teacher ever taught me in any school.

It's written in his hand. He doesn't use notation software. It's him, a pencil, and photocopies of his pencil scores. One thing I didn't know which is interesting is that when he's got a four-piece or five-piece horn section, he has to deal with, it'll be four piece until he gets to the chorus and wants a bigger sound. That’s when he writes seven pieces. Or he writes nine pieces, six or seven, and then he goes back to the four. And he doesn't care; he just gets the guys to overdub.

I got a four-piece horn session, I'm going to write four-part harmony throughout. And it's like, well, no, he doesn't do that. That's like the Steely Dan records when Tom Scott arranged all the horns. He did that, too. I only now realize where it might be two horns starting, and then as it grows, he has a third and a fourth, a fifth, a sixth and a seventh until he finally gets that sound, he wants. But again, social media.

I look at his scores, and they're transposed, which makes no sense because pop guys use concert scores. Classical guys use transpose scores, right? I'm friends with Jerry Hey on Facebook. I figured I’d send him a private message. Hey Jerry, I'm working with Les, blah blah blah, and I can't believe it's you. Jerry gets back to me and explains why he uses transpose score and all this stuff.

No matter what the talk about music is or whatever questions anybody asks me, it always gets back to arranging. Did you ever hear what Burt Bacharach said about his work? He says, "I'm a composer, an arranger, a piano player, and all these things. I get joy out of all of them." He then says, "But the thing that I get the biggest kick out of, more than the songwriting, is when I write an arrangement for orchestra. And I stand up on the podium for the first time, and I count one, two, three, four, and they play, and I hear my arrangement."

Arranging is a thing that people who don't do don't understand. First, the power. You're telling everybody exactly what to play. Like, it's not a jazz group, right? If you're writing an orchestral arrangement or horn, these guys are playing exactly what you wrote. So, it's a bit of a power trip. It's a bit of an ego boost if it sounds good. If it doesn't sound good, you want to slit your wrists.

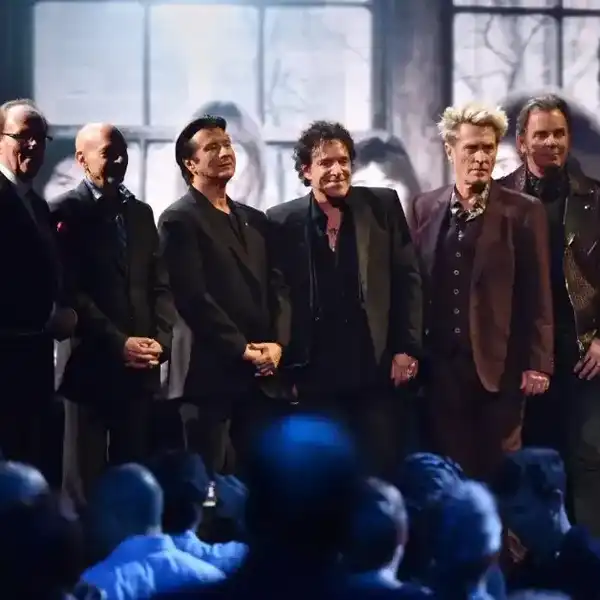

Another aspect of what you do is being a music director for the Rock of Fame show [at Massey Hall]. I remember seeing the ending of this — the finale. You were standing on stage with all these dignitaries from the music world conducting. It looked like you were losing it.

Blissed out because it sounded good.

I did two shows last year at Massey Hall. The Canadian Songwriters' Hall of Fame, where we inducted David Foster, Alanis Morissette, Bryan Adams. More recently, the Rock of Fame show where we inducted 13 Canadian rock bands from the '60s and the '70s. I was the musical director for both shows. I had an extended house band, which is maybe a ten-piece house band, and we back everybody up now.

Do you stress out over this stuff?

Yeah, it’s pretty stressful. The only thing that's more stressful than doing a 'music-centred' shows like these is in the early 2000s doing the Gemini and the Genie Awards. That's live-to-live television, not live-to-tape. All this stuff is live to an audience. Live to air. This means you have the headset on and the director's yacking in your ear, and the stage director is counting you down to going into commercial. They time everything to the half-second. So not only do I have to get everybody rolling and watch what's going on, but I also must do it on stage. I need to complete the music because the logistics of the job will be the challenge. If you're worried about the music, you weren't thinking about timing.

It's like Ricky Miner doing American Idol. That's live to air. That is the most stressful. Next is where I've got 13 artists performing with a house band. That pertains to being a psychologist to some extent because there are people who are extremely terrified. They are not accustomed to performing without their bands. For example, sitting in the front row, we got Serena Ryder to sing "You Oughta Know" for Alanis Morissette. She called me and says, "Lou, I don't think I can do it." She says, "I'm freaking out. She's my idol. When I was 13 years old, and that record came out, I used to perform barefoot in my bedroom in front of a full-length mirror dreaming I was at Massey Hall. I don't know if I can do it for real."

And I say, "Serena, the only way to do this is to put yourself back in that moment. Come out with no shoes on. Think of that mirror and put yourself in your bedroom and do it just like you used to do it.” Afterwards, she thanked me and said," Thank you for saying that. Otherwise, I would have exploded with fear doing it in front of Alanis."