Polaris Music Prize Stays True to Itself After 20 Years: Critic's Take

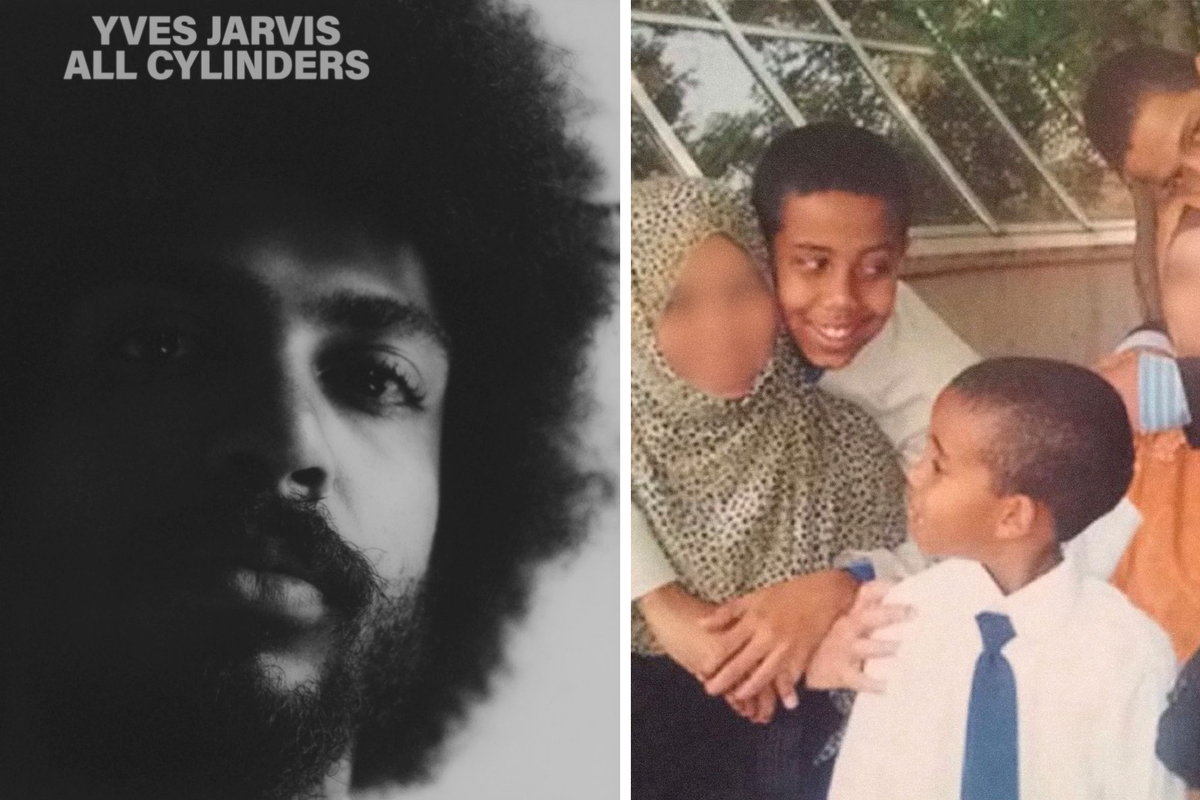

Montreal’s Yves Jarvis won the $30,000 Canadian album of the year prize for All Cylinders, while Mustafa claimed the first-ever SOCAN Polaris Song Prize for “Gaza Is Calling.”

Yves Jarvis and Mustafa Album Covers

For 20 years, the Polaris Prize has refused to compromise. This year's winner is proof of that.

Montreal-based musician Yves Jarvis took home the $30,000 prize for the Canadian album of the year for his album All Cylinders last night (Sept. 16) at the gala at Massey Hall in Toronto and broadcast live on CBC Gem and YouTube.

Jarvis made the album himself after moving back to his parents' house in Montreal from Los Angeles, and he said he suffered a concussion from banging his head on the low ceiling in the spare room where he recorded it.

"I recorded most of it on like no budget, and I didn't even think it was the record," he said. "I feel really blessed to be recognized in this way and be an ambassador for Canadian art."

All Cylinders beat out nine other albums on the 2025 short list, including albums from Nemahsis, Mustafa, Saya Gray, Marie Davidson and more. Almost all of them took the stage to perform, filling the concert hall with sounds from prog to techno to punk and French pop. There was no one album that stood above the rest this year, which made it even harder to guess than usual.

Given its roots as a critics' award inspired by the U.K.'s Mercury Prize, it's often tempting to read into the winning album and see what it represents about the greater landscape of Canadian music. If All Cylinders represented something this year, it was the identity of the award itself. In many ways, the album was everything the Polaris Prize is meant to represent: an award based solely on artistic merit, regardless of label, genre or any other classifications. Unique and uncompromising, the album often sounds like it disassembled the pieces of a rock, funk or psych track and then reassembled them just a little bit imprecisely.

In its early-mid-2000s peak, the Polaris Prize carried considerable cultural cachet. A win for a band like Fucked Up (2009) or Lido Pimienta (2017) could propel an act to bigger stages, international media coverage and countless bar-room arguments. Rapper Haviah Mighty, who won the 2019 Polaris Prize for her independent album 13th Floor, hosted the gala and admitted she didn't know where her career might have gone if she didn't have that milestone.

In recent years, though, the award has been getting similar criticism to its early years when it was considered the "indie prize" — an award that rewards only smaller or weirder acts who could "use the money."

That wasn't quite right in the first year, when it was won by Owen Pallett's He Poos Clouds and it isn't today either. Instead, it's meant to be agnostic to popularity, rewarding the "best" album whether it's made by a totally independent band or the biggest star in the world. Acts like Arcade Fire (The Suburbs, 2010) and Kaytranada (99.9%, 2016) would qualify as "big" acts who could also easily win Junos or Grammys, and many even predicted Drake to win for Take Care in 2012 (it lost to Feist's Metals). The weight of the prize could lift an album into the centre of the critical conversation, at least among dedicated music fans.

If less true now, it's not so much a reflection of the prize as it is a reflection of the landscape of Canadian music and criticism. There are fewer full-time employed music critics or curators to make up the jury or cover the show, and there's less room in newspapers and magazines for coverage of artists that don't already dominate the conversation.

Somehow, the Polaris Prize has been able to sustain itself without compromising its central tenets or methodology. After 20 years of winners, you can't pigeonhole the award to one specific genre or sound, but there is a Polaris style album. It's hard to describe, but you know it when you hear it. Often it feels like All Cylinders: singular, unique, the reflection of an artist or artists following their vision through to the end.

The prize is committed to its jury process. Over 200 people vote on the long and short lists (including me), and the winner is chosen by 11 grand jurors in a room arguing about who most deserves it. It's not about star power or media coverage or any other factor, just that elusive "artistic merit."

More recently, Polaris has expanded that process beyond its central album of the year prize. This year saw the introduction of the inaugural SOCAN Polaris Song Prize, which applied a similar jury process to songs instead of albums.

"What we love about it is that the Polaris jury is applying the same uncompromising standard that they bring to the album of the year to recognize one truly outstanding song," said SOCAN's Cameron Kennedy.

Celebrating a different music form offers a good opportunity to recognize music that might not be recognized otherwise, though maybe its process could use some tweaking: all five short listers were from albums that were also nominated for the album prize.

The winner was Mustafa for "Gaza Is Calling," a song that best reflects the Toronto songwriter and poet's knack for mixing big and meaty themes with deeply personal reflection. It's well deserving of the first award, even if Mustafa couldn't be there to accept it.

Polaris also recognizes albums from before 2006 with the Slaight Family Polaris Heritage Prize. This year's winners were Jane Siberry for her 1985 album The Speckless Sky and Vancouver band The Organ for their sole 2004 album Get That Gun, now regarded as a queer post-punk classic.

Though they are older than the organization, both feel quintessentially Polaris: albums that might not have achieved the same household name status as their peers, but are part of a canon of Canadian albums that shaped the conversation, influenced culture and made their own impact.

It's reassuring to know there's still a place for that.

Guess Who's Coming to Dinner in Toronto on Feb. 26, 2026.Malique Stone

Guess Who's Coming to Dinner in Toronto on Feb. 26, 2026.Malique Stone Boi-1da, Spencer Badu, Hassan PhillsMalique Stone

Boi-1da, Spencer Badu, Hassan PhillsMalique Stone Hassan PhillsMalique Stone

Hassan PhillsMalique Stone Catriona "Coco" SmartMalique Stone

Catriona "Coco" SmartMalique Stone